The Greatest Hockey Series

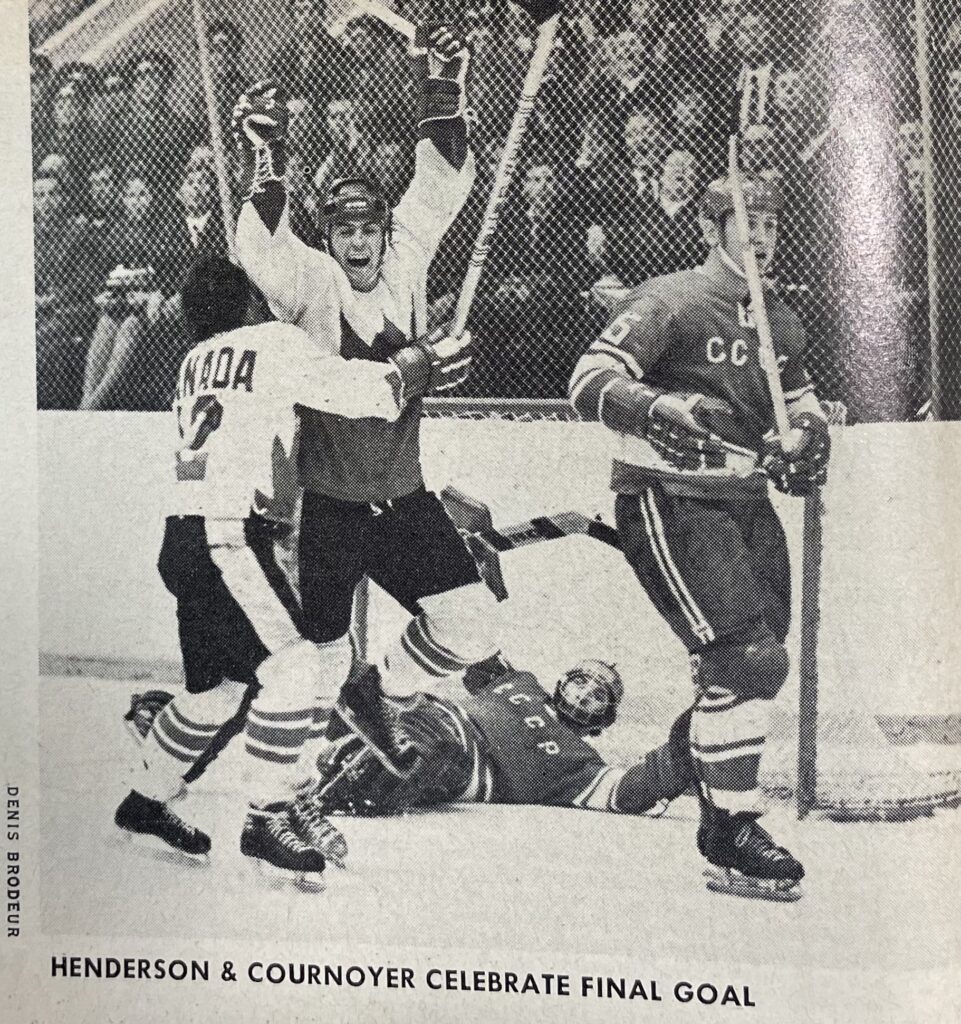

In the summer of 1972 Time magazine assigned me, the Toronto bureau chief, to cover an eight-game hockey series between a select team of NHL stars and the best players of the Soviet Union—four games every other night in four Canadian cities and four in Moscow. Much ink and celluloid has been spilled in the recounting of that historic September confrontation, especially including a goal by Canada’s Paul Henderson with 34 seconds left in game eight that allowed Canada to claim victory in the series. For a nation that invented hockey but had not won Olympic gold for 20 years, the victory was sweet, and vindicated a withdrawal from international hockey in the 1970s because our pros were not allowed to play.

Some commentators later actually elevated the occasion to a turning point in Canadian history. But it was a Pyrrhic victory. Far from the sweep that the North American hockey world had predicted, the Russians won three games, tied one and outscored Canada 32-31. Their superior conditioning and exciting playmaking proved that you didn’t have to be Canadian to excel at hockey.

It was a shock. It also turned into an extension of the Cold War on ice, with both sides seeing it as a clash between two systems, two ways of life. As the fiftieth anniversary of the Summit Series approached in September 2020, Vladimir Putin invaded the independent democracy of Ukraine and, as I write, was on his way to demolishing the country for his own perverted ends.

The war coincided with plans afoot to commemorate the Summit Series in books and documentaries, including my own modest effort to review commemorative books for the LRC, Canada’s leading literary periodical. All of that caused me to return to the Clara Thomas archives at York University, which houses my journalistic files, to dig out my original Time reporting. It is all there, from the first revealing skate by the Soviets at the Forum in Montreal to interviews with key players and observers, including Ken Dryden, Vladislav Tretiak, Harry Sinden, Lloyd Percival — even media guru Marshall McLuhan on the meaning of it all. And, of course, the magic goal. Many gems in the vast file of material did not make it into the magazine because of space limitations and the peculiar TIME system of the day when writers in Montreal or New York wrote and correspondents in the field filed extensive reports.

Here for the first time, then, is everything that I saw and heard — and some things that I didn’t — in a consolidated version, as I wrote it. [When I added additional material, I marked it within square brackets].

Robert Lewis, August 2022

-0-

August 30, 1972

The Background — (Filing from Toronto)

It is, of course, a classic sports meeting. Two different systems of ice hockey are on trial: the methodical team approach of the Soviet state, with the emphasis on the ‘total athlete’; and the innovative style of the Canadians, orchestrated by the NHL and American capitalism.

Al Eagleson, the brash impresario of the Summit, has vowed that Canada will win all eight games. Accordingly, Canada must take them all. The Russians have nothing to lose, especially during the first four games in Canada.

Pravda says it’s nonsense to suggest that there’s anything Canadian about the NHL. The league, says Pravda, is American because it costs $6 million to buy in and “only American businessmen can afford that kind of money.” Canadians, of course, just look at the birth places and they know: Flin Flon and Timmins and Drummondville and Sydney. So beneath it all, it’s an ideological battle. Harry Sinden talks about it as a virtual contest in lifestyles. The Russians regard the match as only a detour from the one, true ‘amateur’ way. For Stan Mikita, who fled Czechoslovakia at eight years of age, it’s “almost like the whole free world versus them.”

“Like the whole free world versus them.”

Stan Mikita

Only through an intense round of international politics, top level diplomacy and back room dealing, was Canada able to direct an end run around the powerful Bunny Ahearne, head of the International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF) and to arrange the Canada-USSR matches. Only through the most intense brand of domestic politics, often pitting Grit against Tory, were the details hammered out.

Ever since the mid 1950s when the Canadian hegemony in international hockey started to crack, Canadians have been frustrated by our inability to use the best from a country against European competition. As their techniques improved, the inferiority of our amateurs and junior pros became all the more evident and galling. And just how deep rooted the anger runs is revealed in a survey by Martin Goldfarb Associates commissioned by the federal government through Hockey Canada. The survey indicates overwhelming support for the decision to withdraw from international ‘shamature’ championships staged by Ahearne. [He and his IIHF will serve as the heavy in this narrative]. And one of the central themes of the survey was: if we can’t play our best, why bother?

In an interview [not used by TIME] Marshall McLuhan noted that sport and politics have wed — and Hockey Canada is exhibit A. The media prophet points to “the ping-pong-ding-ding-Peking” [table tennis matches], the Fischer-Spassky chess summit [which the American won] and now the U.S.S.R. hockey series as a pattern. McLuhan submits that the link between politics and sport is essential in the electronic age. People can’t take their politicians, or their politics, straight anymore. “Politics,” McLuhan theorizes, “must now be indirect, not direct, because that’s the only way to cool them.”

Adds McLuhan: “We are getting a cool form of international politics on the game front. The heat is syphoned off through audience participation. In politics, the audience doesn’t get a chance to participate: the ballot box does not really permit participation. That’s where sports have this tremendous power of catharsis. Sports also happen to be a very aggressive and destructive form of expression that is also very congenial to political life. But it’s cooled-off warfare. It’s warfare under wraps. It may be the only kind permissible from now on. The Olympics, of course, are all politics. We’re going to discover the Soviets and others, with their entirely professional set ups in sports, are going to be irresistible. And so are we’re going to imitate them.”

Doug Fisher, the former MP and an architect of the series who later chaired Hockey Canada, was speculating the other day along similar lines. “Guys like [NHL owner] Jack Kent Cooke will see the potential of all of this,“ he muses. “They’ll be into it very quickly in the United States. “ [Before his death in 2009, Fisher recorded his own extension account [not yet posted] of his involvement in the negotiations that led to the series].

The Trudeau government is not unaware either of the benefits of association with Hockey Canada and the selects. As far back as June 3, 1968 Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau told an election campaign meeting in British Columbia’s Selkirk College that he intended to launch a wholesale review of sport in Canada. And when Harold Rae, the task force chair credited with coming up with the Series idea, champion skier Nancy Green and Montreal lawyer Paul Wintle Desuisseaux were named to the study, Trudeau reflected the thoughts of many Canadians when he said: “Hockey is considered our national sport. Yet in the world of hockey championships, we have not been able as amateurs to perform as well as we know we can.” John Munro, Trudeau’s minister of sport, effectively orchestrated the birth of Hockey Canada and recruited Fisher to the cause.

In more recent times, activity on behalf of Trudeau indicates he’s cribbing from McLuhan. Bargaining went on about the Prime Minister’s appearances at the Montreal and Toronto games. Clearly he wants a cool ride on Hockey Canada’s coattails.

Trudeau wins the puck drop

Trudeau wins the puck drop

Prime ministerial operatives are seeking to escalate the Saturday night puck dropping ceremonies in the Montreal forum into a full-blown production. The PM, for example, [according to Art Harnett, president of media rights holder T.C. Productions] wants to do French and English interviews between the first and second periods. In Toronto, Gardens officials were sent scurrying this week with the news that the Prime Ministerial party would require 50 seats for next Monday’s game. The PMs staff also insisted on moving the official party from behind the Gardens’ penalty box to seats behind the players benches which, wonder of wonders, just happened to face the television cameras. Trudeau was also holding out for a starring role in the Toronto puck dropping ceremony which all those good Tories in Toronto felt was a part that should be played by Ontario Conservative premier Bill Davis.

Personal politics is a vital component to the series. Harold Ballard, for example, who awaits sentencing on fraud charges, has wrapped himself in a mantle of national pride. He gave team Canada free use of Maple Leaf Gardens for the three week training camp and is spending his own money just to turn the TV lights on in his rink for practice sessions [the heat clears the fog that tends to hang over the ice in the current steamy weather]. Ballard has also seen to it that all announcements made during the Toronto game and during the three inter-squad matches are bilingual. “Ballard,” notes one hockey regular, “can’t afford bad publicity at a time like this. “

But nowhere were the stakes higher, and the intrigue more sophisticated, than in the international arena of world hockey. Not long after Hockey Canada was formed in 1969, a Canadian delegation travelled to an IIHF meeting in Cranz in June. Hockey Canada proposed an “open” competition between the best of Europe and a Canadian team using 12 pros. In the end, Canada had to settle for nine non-NHL players among the pros. The Winnipeg-based national team thus entered a tournament in Leningrad, bolstered by pros, and became the first Canadian squad to win against the Russians since the Trail Smoke Eaters won the World Championship in 1961. A couple of months later, Canada took second place in the Izvestia tournament.

In January 1970, however, Bunny Ahearne’s antipathy to Canada’s hockey policy prevailed at an IIHF meeting in Geneva. The league decided that five European clubs scheduled to play in the world championships in Canada in 1970 would not participate because of the new ground rules allowing Canadian pros. Canada replied that unless it could play some professionals, it would not participate either. But Canada did offer to stage an exhibition tournament, using some professionals. When that was rejected, Canada felt it had no course but to withdraw from international play. The Canadian delegation, in fact, had already agreed before leaving for the Geneva meeting that if the IIHF proposed to ban the use of pros by Canada, Canada would quit.

Despite the withdrawal, oil man and Hockey Canada President Charles Hay was back in Stockholm in March for the IIHF meeting. “I was just there sticking my nose in,” he smiles. But he also had a firm proposal: an “unrestricted“ series of exhibition games involving Canada, Sweden, Finland and others. The IIHF rejected the offer.

Back home in the summer of 1970, Hockey Canada took what proved to be an historic and important step: it formed an IIHF negotiating committee, chaired by Doug Fisher and including the CAHA, which was really the only official link that Canada had to the world hockey body. The Canadian committee, as it eventually turned out, provided the respectability the Russians needed before they could agree to the current series. They did not, in short, want to bypass Ahearne and his IIHF. It was then-Toronto Leaf president Stafford Smythe who suggested that Canada challenge members of the IIHF ‘A Pool’ of top teams in a round-robin tournament in Canada. There was a positive reaction to that suggestion, but the Europeans expressed confusion about which teams they could send to play.

In December 1970, with the impasse continuing, Hay and Gordon Jukes of the CAHA went to Moscow for the Izvestia tournament in which the Canadian national team placed second. They pursued their challenge to Russia, Sweden and Czechoslovakia to come to Canada for a round robin tournament. By that time some important groundwork had already been laid in Canada for the series: the Hockey Canada board, NHL President Clarence Campbell and Eagleson agreed that if Hockey Canada could produce an open, international round robin, the players’ association of the NHL would cooperate.

In March 1971, the Canadian proposal went before an IIHF meeting in Geneva. Only Sweden and Russia were interested in the exhibition, it became clear. But the IIHF, which was by now in the thick of negotiating the Canadian proposal, countered with a three-pronged response. Because the IIHF wanted to avoid a single round robin with Canadian pros, they proposed a return trip to Russia by the Canadian pros; a Canadian entry in the ‘B Pool’ of the IIHF championships — a division normally reserved for such hockey powers as Japan, the Sudan and New Zealand; and a tour of Russia by a Canadian amateur team.

Clearly Canada could not accept such an affront. Never before had Canada been relegated to the ‘B Pool’. But as Charlie Hay notes about Ahearne’s gambit: “He wanted to bring us to our knees. Our scheme was an erosion of his position.” Canada rejected the counter offer.

Later in May 1970, Ahearne visited Canada, trotting out his ‘Olympic purity’ bugaboo and being generally unpleasant about Canada’s role in hockey. Despite his public displays of uncouth, Hay stoically entertained Ahearne. One veteran hockey insider quipped: “If there is one thing that Ahearne admires, it is money.“ And here, dealing with the former president of Gulf Oil in Canada, Ahearne must have realized he had found a worthy opponent in Hay, the father of former Chicago star Red Hay.

Next came the winter Olympics and, as Hay puts it, “another political labyrinth.” The IIHF ruled that unless Canada entered the world hockey tournament in Berne, it could not play in Olympic hockey in Japan in 1972. Canada refused to bite. But the Japanese wanted Canadian hockey players at the Olympic games. An invitation was extended and Ahearne, apparently realizing he was about to be had, said he could approve the invitation. Again, however, Canada said no. “It wouldn’t really have settled our objective to get a top team to play the Russians,” Hay explains. Naturally the decision not to send a hockey team to the 1972 Olympics produced anger in Canada. But for Canada to have entered either the 1972 world championships or the Sapporo games would have amounted to a negation of its earlier posture — withdrawal until we can play our best.

Canada then formed a select committee which included Hay, Lou Lafaivre, head of Sport Canada, and Joe Kryczka, a Russian-speaking lawyer who was president of the CAHA [Canada’s formal connection to the IIHF]. That is an important connection to the Russians since they are firmly committed to retaining their standing in international hockey and the CAHA’s links to the IIHF enable them to accomplish that. At the same time there was full and close contact between Hockey Canada and Canada’s External Affairs department.

Canada’s Ambassador Robert Ford in Moscow, and other emissaries in Europe, beat the drums on behalf of the round robin tournament Canada wanted to host. Ford, or his agents, also leaked word that a one-on-one series with the Soviets was a possibility. The Soviet response was one of enthusiasm. [A key man in the mix was Canadian diplomat Gary Smith who first learned of the Soviet interests while reading a sports column in Izvestia. That story forms part of the book he published in spring 2020 called Ice War Diplomat. Smith travelled with the Soviet team in Canada and was an indispensable link here and in Moscow between Canadian and Russian players, officials and press, including this reporter].

In March 1972 in Prague the culmination of months of negotiations produced an inconspicuous-looking agreement, single-spaced over a page-and-a-half with no letterhead. The headline: “Unrestricted tournament.” The document described four games here and four games there. The final talks had taken only ten days. [For more on the history of Canada’s participation in International hockey, including the years when we dominated, see Appendix I, not yet attached].

August 31

The Teams — (Filing from Montreal)

Professional hockey is machismo. The forms that scouts carry with them into the hinterlands have boxes for rating a prospect’s willingness to defend himself (sometimes called “guts”). Off the ice, players and coaches sometimes startle cabdrivers and bellboys with sharp orders that are no more aggressive than their lifestyle on the ice, but which are offensive to the untrained ear. In hockey, notice, you “get up” for the big game. Women’s role in organized hockey is virtually nil. Yet women serve as window dressing at training camps, and lobbies – and in not a few NHL hotel bedrooms.

The Canadian selects seem driven by the same macho-macho. While they pay lip service to “representing Canada” in this series, you sense that they are really here to prove themselves with the class of their profession and to preserve the honour of the National Hockey League. In perhaps a dozen casual conversations with players, rarely did they volunteer national pride as their first motivation. Says articulate Canadian goaler Ken Dryden, who will probably start the Montreal game Saturday, “we’ll have the same feelings of team and personal pride. The immediate motivation is to play well and win.”

The Russians, in contrast, say they are here primarily to learn. “What we’ve got to do is make the most of this series,” said one Soviet official on arrival in Montreal last night (August 30). As for the Canadian selects, they have to win. About 22 million Canadians, as Coach Harry Sinden notes, are “absolutely demanding it.”

While several players reckon the tension will be no greater than the final game of the NHL playoffs, Sinden and Ken Dryden disagree. “You’ll be remembered for a year for beating Russia,” says Sinden. “You’ll be remembered for the rest of your goddamn life if you lose. That’s pressure, baby.” Adds Dryden, who played against the Russians for Canada’s national team, “even if you’re not a patriot or a nationalist of any kind, the whole pageantry of the thing is such that you can’t help getting emotionally involved.”

Lloyd Percival, one of Canada’s top hockey tacticians and director of Toronto’s Fitness Institute (which specializes in training programs for professional athletes) warns that the Canadian pros may not be prepared for the tension surrounding this series. “No athletes carry the emotional load that team Canada will,” Percival told us. “The reputation of the NHL is at stake. If we don’t win eight straight, it will be a moral victory for them. I’m concerned we’ll be over-emotional. We might be too tight, press too hard and start taking penalties.” In Percival’s lingo, the danger is that Canadian players could become “over–activated.”

In rating and weighing the various facets of the two teams, Percival gives Canada an overall five-point edge and predicts we’ll win the series on the basis of great individual offensive abilities and superior goaltending.

The Russians are expected to base their strategy on attack. They will start off at a fast pace and, unlike the NHL style, attempt to keep at the tempo throughout the game. Since the Russians are given the edge in conditioning, this could be important if they can keep the puck. In international play the Russians have little difficulty sustaining the brisk play: they usually have the puck 70% of the game. Against the Canadian pros, however, they may find that can’t be done. For the first time in their history, perhaps, the Russians will experience that uncomfortable sensation of defending in their own end against a sustained, two- to three-minute attack. In international play their opponents have generally managed to take only one shot, with the Russians breaking out of their end of the rink immediately.

The Russian attack will also cause the NHLers complications. The pros tend to play positional hockey on defence, with each man patrolling his “lane” of the ice to pick up his check. But the Soviets don’t skate such predictable offensive patterns. The right winger, say, might lead an attack on the left side, with the centreman trailing behind him. On defense, however, the Russians are expected to play a kind of zone. “They aren’t going to be out there playing man-for-man,” predicts Percival.

Another difference in the two styles is passing. NHL players tend to pass to an open man; the Russians will pass to get a man open. Since the Canadian selects include so many class players who tend to make the game look pretty, there may be a tendency for Canada to pass instead of shoot. This is one of the points on which Sinden has been most critical during the three week-training camp. After Saturday nights intra-squad game, for example, Sinden moaned: “Two or three times we dropped the puck when we should have shot. It was laziness. They should have headed for the goal.”

In more detail, here is a look at the two teams, their coaches, players, methods:

The Russians

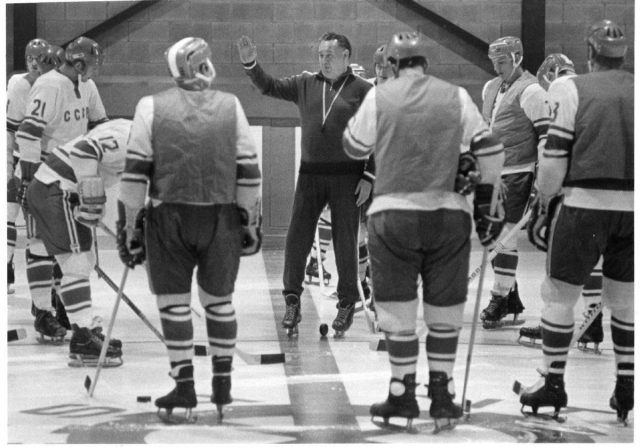

A majority of the Russian selects played for the central Army team. Like most senior players in the Soviet union, the selects started training with their respective clubs in July. Several weeks before they actually take to the ice, the Russians launch a vigourous program to train the complete athlete. Under the “Tarasov plan” (named after the so-called ‘father of Soviet hockey’, Anatoly Tarasov), they play soccer (NHL contracts bar contact sports in the summer), lift weights to build bodies (the NHLers concentrate on drills to improve wind and legs) and work out on the trampoline. [Since this was written 50 years ago, critics insist that Arkady Chernyshev, with 11 World and four Olympic championships is the godfather of modern Russian hockey].

On August 21 the Russian selects gathered as a team. They had already played in two tournaments with their own clubs. With so many players from the central Army team and another top line (Yakushev-Shadrin-Zimin) from the Spartak club, the Soviet players didn’t have to worry about adjusting to unfamiliar styles. (The Canadian team, on the other hand, claims only one complete line from one team: Hadfield-Ratelle-Gilbert).

A tentative list of the Soviet roster provides outsiders with another revealing glimpse of the kind of confidence this team should have: many of them are veteran international champions, often with three world championships and two Olympic victories behind them. As Sinden warned his players this week: “It’s not going to be a howdy-doody time against the Russians – no way.”

Ken Dryden knows that from personal experience: after meeting the Russians in Stockholm when Canada’s National Team last appeared in the world championships, Dryden was back in the nets in Vancouver to face the returning Russians in 1969. “They completely control the puck,” he recalls. “The only times the Russians didn’t have the puck was when the referee was carrying it back to centre right after they scored.”

Dryden concedes that comparisons are difficult, since Russian and Canadian pros have yet to play common opponents, or each other. He does look for more passing from the Russians than in the NHL. “They pass more, we shoot more, and harder. You have to adjust since you don’t get as many shots.”

In 1968 another member of the Canada selects, defenceman Brian Glennie, was in Grenoble where he played the Soviets in the Olympics. “Many of the Russians,” he notes, “have been mates for eight to ten years. That means they function well as a unit. They are strong in the most basic skills of the game and they’ll be in good condition.”

Glennie also notes that the Russian players attempt to goad opponents. “They are very chippy with their sticks. They take cheap shots.” Says John Ferguson, the assistant coach: “They give you that little jam and run.” When a reporter told Sinden about claims that the Russians sometimes spit on opponents skating by, Sinden was horrified: “Could you just see that. “Maybe we could present them with gold spittoons after it’s over.”

The real danger, of course, is that Russian goading of some kind may draw reflexive retaliation from the NHL stars — and very quick penalties. Fighting, for example, means a player is thrown out of the game. Obviously the Soviets will try to lure Canadians into stupid penalties, another reason the tension may work against Canada.

One widely held misconception is that the Russians can be intimidated by hard body checking. That is not a view shared by most of the Canadian team. “They are very strong and you can’t intimidate them,” says Glennie. Instead of intimidation tactics, Glennie advises a solid, physical approach — again, a thin line in a tension-packed series where the international officiating will favour the Soviets. The Russians, clearly, will avoid fights. “If they want to fight,” said the imperial Arkady Chernyshev, one of two Russian scouts in Canada watching the Canadian training camp, “We’ll do it later in the gym.”

Harry Sinden, who played in Oslo for the Whitby Dunlops when they won the World Championships in 1958, has some personal experience with Soviet hockey. He also faced the Russians during their first Canadian visit. “The main difference in their play,” he comments, “is the same kind of difference between their way of life and ours. They are a disciplined society and they play disciplined hockey.” When Phil Esposito was asked why NHL pros tend to sleep late, drink beer and smoke cigarettes, he quipped: “That’s their problem if they want to get up at 6 AM and run around the hotel.”

Since there are only four Canadian selects (Sinden, Dryden, Glennie and defenceman Rod Seiling of New York) with personal experience playing against the Russians, Sinden planned late this week to start going over film of Russian games with his charges. But, he notes, Canada can watch all of the films available and it still won’t be as instructive as the actual meeting of Canadian and Russian on ice. “We won’t know what we want to know about the Russians until we play them,” says Harry. “Not until we’re up close in the corners while we see their strength and attitudes.”

-0-

The scouting mission by Leaf coach John McClellan and scout Bob Davidson, in sharp contrast to the visit in Canada by the two industrious Russian ‘spies’, amounted to a little more than a goodwill tour. The Canadian ‘spies’ were only in Moscow four days and saw only two games: Spartak versus the Central Army team in Leningrad and an inter-squad game involving the Soviet selects. Spartak beat the Army team 5-2. Davidson was impressed by the way the Russians pass the puck. “They really play together as a team,” he notes. “They rarely go offside. They’re in good shape.”

Players that stood out in the brief look Davidson got were Shadrin, Yakushev and Zimin. Centreman Shadrin impressed Davidson with his forechecking; Zimin, a short, stocky right- winger, will have to be watched: he has a tendency to hang near the centre ice line, à la Yvon Cournoyer, waiting for a breakaway pass from his own end. Yakushev was outstanding in the two games. He is a good skater and puck handler. “He seemed to be dangerous whenever he had the puck,” says Davidson. Forward Maltsev with another player who impressed with his skating and puck handling.

One problem the Russians may have is in the net. They have already lost their number two goaler, Vladimir Shepevalov because of a pre-series injury. The starting goaler, Tretiak, is long and lean. Typically, for Russia, he uses his legs and is a flopper, rather than a positional player. The suspicion is that he can be beaten on blistering drives from 30–40 feet out. [That subsequently proved to be incorrect. Tretiak played all eight games and was a star of the series. It turned out that the Canadian scouts happened to see Tretiak play poorly the day after a prenuptial carousing with his mates].

Sinden ranks Valeri Kharmarlov as the team’s scoring star. He’s a good puck handler and, because of his small size, resembles Team Eagleson’s Gilbert Perreault. Veteran Anatoli Firsov, apparently, was injured recently and is not expected to play in the games in Canada.

The Canadians

Never has a finer group of hockey players been assembled anywhere in the world for one team. There are 37 in all, ranging from the obvious stars to the journeymen known mainly to insiders. Ironically the two most obvious starters – the Bobby’s Orr and Hull – won’t be in the lineups (at least Orr won’t play in Canada).

It was June 1 when Harry Sinden first started putting it all together. That was the day Al Eagleson, in his capacity as impresario of the first international Eagleson tournament, offered Harry the coaching job.

Working in Sinden’s favour is his past Olympic experience and his reputation (he coached the Bruins to the Stanley Cup in 1970) as one of the NHL’s new breed of mentors. “Sinden has a modern hockey mind,” says Lloyd Percival. “He’s not the traditionalist that so many coaches are. He’s proven he can handle stars.”

A week after his selection, Sinden turned to John Ferguson as his assistant. Fergy, along with Jean Beliveau, was a driving force behind the Montreal Canadiens in recent seasons. Like Sinden, he was not attached at the time to any NHL club. (Sinden was working with a modular housing company in Rochester, NY, which is about to go under and Fergy is prospering with a Montreal clothing manufacturer).

By July 12, Sinden had picked his last player (although five of the originals, including Hull, turned up in the rival WHA and were barred at he insistence of the NHL). “The first dozen or so players,” notes Harry, “more or less picked themselves. Any armchair hockey coach from Victoria to St. John’s could tell you who they are. The last few were the hardest, not because it’s impossible to find 35 world-class players in Canada, but because it isn’t.”

The key, once stars like Esposito, Cournoyer and Hadfield were named, was balance. Sinden chose for specific situations: for the clutch face-offs there is, for example, Stan Mikita—a late replacement for WHA-bound Derek Sanderson. For versatility there are Wayne Cashman and Jean-Paul Parisee: they can play right or left wing and, while neither is a scoring star, they are solid in the corners. There are shot-makers like Brad Park and the shot-blockers like Don Awrey. There is the finesse of Phil Esposito, Jean Ratelle, Bill Goldsworthy and Frank Mahavolich to go with the workmanship of Parisé and Ron Ellis (one of the most consistent performers in the camp so far) and Peter Mahavoilich.

In goal, what can you say about Ken Dryden, about to start his second year as Montreal’s starting netminder, Tony Esposito and Eddie Johnston? Dryden will probably start the first game, because of his previous International experience and because Montreal is home. Esposito has actually looked sharper in the training camp. Teamed with Johnston, Dryden and Esposito hold one of the keys to the expected Canadian victory. Only when the play moves to Europe, and the circular goal creases, will the Canadian goalies face a major adjustment: Esposito, particularly, likes to use the rectangular North American crease for establishing the proper defensive angles on shots.

The team arrived in camp in amazingly good condition. Most of the players were on notice about their possible selection. Because many are involved with hockey schools, and others took part in vigorous training programs (Henderson, for example, enrolled at the Percival school), there was probably less flab than at the routine NHL training camp. Because these athletes are best in the world at their trade, Sinden had little difficulty with motivation.

For just about every day now for three weeks, he has sent his men through twice-daily skating sessions, scrimmages and drills. Exercise sessions preceded each morning practice and Sinden altered the pace with three intra-squad games, a Sunday golf outing and the occasional once-a-day work out. Says Ken Dryden: “It’s the best camp I’ve ever been to. You have 35 of the best players on the same ice surface. They have pride in their ability. You’re literally forced into working hard. These people are just too good, day-to-day, to have it any other way.”

Sinden’s prime concern as the camp opened was conditioning. He worked hard on toughening up thigh and leg muscles. There were, as a result, very few of the customary early-season groin pulls. In fact, Sinden let more players off from occasional practices to return home on business then there were people missing because of serious injuries.

Says Percival of Sinden’s squad: “It’s the greatest collection of hockey players we’ve ever had in one place. Potentially it’s the greatest team ever.” The biggest question mark, as we’ve noted, Is whether they can maintain their poise and prevent the Russians from setting the game tempo throughout.

Sinden is anxiously awaiting the first game, which the experts view as the most important one. “We’ll have to see in that first game whether we are going to be able to play regular shifts. (Sinden may have to use shorter shifts to offset the Soviets conditioning advantage). If we let the pace slow down, we could be in trouble,” says Sinden.

And another question mark Involves the kind of physical game Canadian pros normally play. So far there has been very little single ‘hitting’ by the Canucks. “People who are new teammates,” explains Sinden, “don’t want flareups in the early part of the camp.” Adds Fergy: “They are just teammates right now. They are playing for Canada.” But against the Russians, the pros are expected to start throwing their weight around. “There’s no way you can play this game without hitting,” opined Fergy with a gleam in his eye. “You can’t play this game without being mad. I’m sure we’re going to be hitting the Russians.”

“I’m very concerned about the officiating,” says Sinden earnestly. “The kinds of things we do , like slamming guys into the boards, are not allowed in international play.”

The Brothers Impassivov

Each day they sat in seats at Maple Leaf Gardens, flanking their interpreter, filling their notebooks with numbers, names and even diagrams of routine skating drills. When John Munro, minister of sport, sent word during one session that he wanted to meet with them, the reply was: “Wait ’till practice is over. We don’t want to miss anything.”

Such industry, of course, has made the Soviet Union the world hockey power it is today. As Arkady Chernyshev, the tall, suave hockey scout, and Boris Kulagin, the stocky, stoic assistant coach of the Soviet selects, would tell you, such eagerness to learn as much as they can about NHL hockey is routine. Even when the players weren’t skating on ice, Arkady and Boris — dubbed the “Brothers Impassivov” because of the dearth of useful information they imparted — were asking questions: “Who is Eagleson?” Lewis: “He is number one. This is his show.” Kulagin (smiling and making another entry in his notes book): “Who is Bob Haggert?” (Eagleson’s assistant and administer for Team Canada.”

When the Brothers Impassivov visited with Lloyd Percival, they claimed to be impressed with Sinden’s conditioning methods, but they couldn’t understand why the pros were allowed to smoke and drink beer. “I’m sure,” Sinden laughed, “they think our morning exercise program is a joke.”

They probably did, but Boris and Arkady weren’t saying. In typical Soviet style every invitation produced some bargaining. When they were invited to watch a soccer game in Hamilton, they countered with a request to watch a professional football practice. When they were invited to an Argo game, they indicated a preference for the team’s practice.

The Soviets, you see, have a concept of “athleticism”. What goes on in practice is just as important as results in the stadium. Clearly Boris and Arkady were trying to measure Canadian sport from this perspective. Perhaps the only occasion when the Russians went unrewarded was their visit to a Toronto theatre to watch Marlon Brando in The Godfather (they also saw The New Centurions). Explained Del Olah, a peanut butter maker from Toronto who served as interpreter: “They didn’t understand what was going on. They said that there’s no Mafia in the USSR. After three hours of translating, all I had was a headache.”

When Sinden hosted a cocktail party for the two Russians, Chernyshev graciously acknowledged: “We don’t want to conceal the fact that we like Canadian hockey.” But he added protectively: “The result doesn’t matter, as long as it brings about greater understanding between the two countries.”

Throughout, the Soviets have squelched speculation that a Russian team might someday soon end up in the NHL. The Soviets are intent on preserving their international status. Said Chernyshev: “We don’t see any need to enter the pro leagues because our own hockey is developing well.” [Chernyshev’s outstanding coaching record included 11 World and four Olympic championships]. Would a Canadian rout force an evaluation of the Russian program? “It would cause us to make corrections,” replied Chernychev. Then, smiling broadly, he asked: “If the Canadian team is beaten badly, would Canada go back to amateur play?” All the fancy footwork doesn’t conceal the fact that the Russians have always gone about hockey at their own speed (just as they try to do on the ice). They stayed away from international competition until they knew they could win. The suspicion is that when they determine that they are in the NHL class, they will be more approachable.

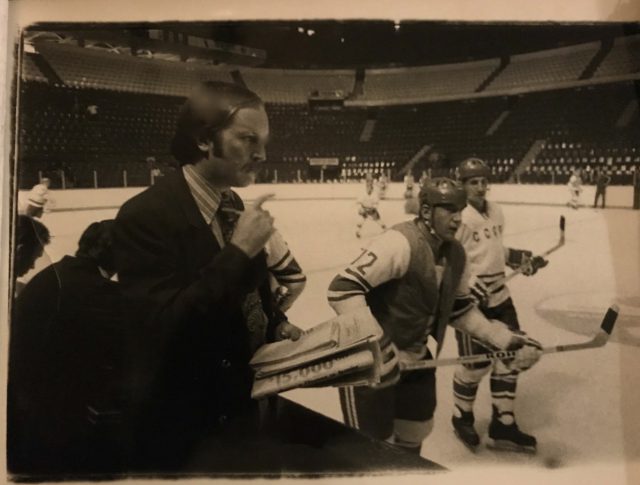

August 31 A First Look — (Filing from Montreal) Those Russians certainly can skate. For more than an hour this morning at the Forum, the Russians roared up and down the ice. Without bothering to warm up, as our pros do, the Soviets moved right into end-to-end rashes: sometimes two on one, sometimes four on three, even six on two. Basically that’s all they did the entire practice, except for a few minutes of stops and starts.

The skating wizardry is all the more amazing given the Russian hockey equipment. The skates are a rag-tag assortment, many decaying CCM models from Canada. A Lang skate rep. attending the workout said he spotted a pair of Canadian skates that would sell for about $20 here ($135 today).

The Russians don’t seem to use tape, either. They wrap their skate laces around their ankles, just like thousands of Canadian kids used to do. Around their shin pads most of the Russians wear garters – again a throwback to the Hot Stove League.

Underneath their red and white uniforms, however, the Soviet nationals wear the best available: Cooper equipment from Toronto, the most commonly used stuff in the National Hockey League. The sticks are mostly from Finland (KOHO), but a few players carried Canadian models. One of their goalies sported what looked like a modified baseball catching mask.

If the pace of the workout this morning is indicative of the game tempo, Harry Sinden has reason to worry “about the pace they’re likely to play.” Sinden reiterated that “we’re going to try and play the game the way we always do.” But fully anticipating the continued high tempo, he added: “I’m glad we have four lines.” [Most NHL teams then played a game with only three sets of forwards].

There is some feeling developing around the Forum that the Russians may be underrated. “If I were a sports writer,” says Sinden, “I’d pick the Russians. Like them, you have nothing to lose.” Working against the Soviet team, however, is the fact that it is in the process of rebuilding — ever since Tarasov was sacked as coach. Several of the 27 member squad, like Ragulin, have been around for years. [In fact, the Russians arrived with a fast-skating “kid line” and, in aggregate, were younger than the Canadians].

Despite the heavy odds against the Russians in this series, there is little doubt in many quarters that it won’t be long before the Soviets are a match for the NHL. “No matter what happens in this series,” predicts Toronto star columnist Milt Dunnell, “I have no doubt that in 10 to 15 years we’ll be going over there trying to regain the Stanley Cup. They have the population to recruit players. They don’t have the diversions we do, like swimming pools and automobiles.”

As the big game approaches, the Canadians are edgy. “They wish the game was tonight, not Saturday,” says coach Sinden. For his part, Al Eagleson went further out on a limb when asked if one Soviet win is a moral victory. “Sure it is,” he replied. “We don’t want to lose anywhere.” Adds defenceman Brad Park: “You could say that if the Russians win one game it will be a moral victory for them.”

On another front, officials were busy hassling with protocol matters. The Soviets, for example, insisted on the musical version of their national anthem — not the version with lyrics that praises Stalin, they decided. Since the piece runs to three minutes and 10 seconds, the producers were desperately trying to find a way to fade the anthem out and leave time for at least two commercial messages, the Canadian anthem and opening ceremonies.

Trudeau will drop the ceremonial first puck in Montreal. But because of the impasse between Tory Eagleson and the PMs office, there will be no official puck dropping in the other three Canadian games. Eagleson had proposed that Trudeau would drop the puck for the first game. Ontario premier Davis would perform the honours in Toronto. And NDP premier Schreyer would do the honours in Winnipeg while the premier of BC wanted to play the role in Vancouver. No way, the PMs office replied. The PM, they said, wanted to officiate alone in Toronto. When Eagleson proposed that Trudeau and Davis do the job together, negotiations broke down.

We have gone over with Eagleson the breakdown of the take from the series: $750,000 will go to Hockey Canada for the TV rights; $1-million to CTV; about $150,000 to agencies for commissions; and $150,000 for insurance, offices and production. Eagleson’s hope is that in addition to the $750,000 guarantee to Hockey Canada, he can add an additional $250,000. This would bring Hockey Canada’s pot to $1 million [$6.8 million today] to be split 50-50 between the hockey body and the players’ association. [Rights holder Ballard-Orr will glean profit $1.2 million]. The Russians themselves are proving adept at North American capitalism. They propose to sell the television rights in the US for the four Soviet games at $50,000 each. Since only one of them is in prime time, Storer Broadcasting of Boston said no, countering with an offer for $65,000 total. The two sides are still bargaining.

Game 1-(Montreal) During one of the commercial breaks tonight in the Canada Russia game, the organist played I’m Dreaming of a White Christmas. Just about that time, the Canadian team must have wished it was mid-winter. Clearly they were not skating at the form they usually are around December.

“We got beaten,” coach Sinden noted after the game, “by a much better hockey team.” What surprised most people about the Russians were some great individual playmaking and goaltending.

Too often Canadian defenceman sprawled on the ice to block shots that never came. Even goalie Ken Dryden, who’s more accustomed to the Russian propensity to pass rather than shoot, was ‘deked’ out of position on a couple of goals.

Russia 7-Canada 3

As for goaltending, well along with individual play, that was supposed to be a plus for Canada. Not tonight. Vladislav Tretiak made at least nine (as I counted them) steals off point blank shots: three by Frank Mahavolich, two by Esposito, one by Peter Mahavolich, one by Lapointe and — most surprisingly — two against the Canadian power play.

“We didn’t shoot enough,” moaned Phil Esposito, referring to the 34 shots the Canadians fired (vs. 30 for the Russians).

What was working for the Russians, clearly, was their superior conditioning and their poise. Many experts had warned that the Canadians might find it difficult to make the adjustment to international hockey. Brian Glennie, who knows from personal experience as a former player for the national team, explained after the game: “Until you’ve played for your country, you don’t realize that you can ‘get up’ too much.”

As a result, the Canadians had a tendency to want to do too much — by trying to be in too many places on the same shift, and by trying to hit everything that moved in a white jersey. But, as Sinden noted, “they take body checks real well. They’re bigger than you think they are. You can’t hit them just by running around.”

As expected the Russians tried to play the game flat out. Sinden anticipated this, but notes: “I really didn’t expect them to skate so easily for the full 60 minutes. Unless we play excellent hockey it will be life and death to win any of the games.” Conceding he would have liked to see more shooting from Cournoyer and that he was disappointed with the Ratelle line (“they didn’t skate at all”), Sinden added: “We’ll make some changes.” It is probably a safe bet that the likes of Stan Mikita and Dennis Hull, who didn’t play tonight, will see action in Toronto).

I was stunned by how well they played

Harry Sinden

It was a point underscored graciously by Russian coach Boris Kulagin: “We realized that not all the best players, like Mikita, Stapleton and White, were in the game.”

Says Sinden: “I was stunned by how well they played at times.” Toronto Sun columnist Jim Coleman agreed, adding that this Russian team is “10 goals better” than when he last saw them at the World Championships. In some ways, as we’ve already noted, it was easier for the Russians to be poised tonight: they had nothing to lose. But no one expected them to win 7-3. The Canadians were just not prepared for the exciting play of the likes of Valery Kharlamov (two goals, including the winner, and named the Russian star of the game), Alexander Maltsev (two assists and several stiff body checks), Eugeny Zimin (two goals) and Alexander Yakushev (a goal and two assists ). “They wouldn’t let us stop to regroup,” said Don Awrey. Added Phil Esposito: “I was really surprised by the goaler. He stoned me as well as anyone has. Their ability to stickhandle surprised me. They’re a really good hockey team.”

How about their defence, Esposito was asked: “That’s hard to say because I was never down in their zone it seemed.”

Dryden, for his part, underlined the tension experienced by the Canadians, as Lloyd Percival and others had predicted. “We played a panic kind of game,” said Dryden. “We’d be behind, then we’d have three men on the park.” Even Mr. Cool, Phil Esposito, conceded he faced a new kind of pressure tonight: “This is probably the first time in my life that I was really nervous.”

As for Eagleson, well he was eating crow tonight. He had predicted that the Canadians would win all eight games. Tonight he had a weak reply: “Now we have to win seven to one.” Eagleson, with prodding, added: “Sure it’s a moral victory for them.”

It was vindication too, one might say, for the way the Soviets have always approached hockey. They didn’t ice an international competitor, for example, until they must have known they could win (which they did in their first world championship in 1954.) Presumably the Russians were equally confident about their match with the pros. My feeling is that they were sure the pros wouldn’t take them to the cleaners and, on the basis of tonight, they were probably right.

The Russians also seem to outclass the Canadians in sportsmanship. When the Soviets lined up at their blue line for the traditional post–game salute, all but three or four Canadians were in the dressing room. Sinden made an effort to get his team back on the ice, but it was too late. The Russians had left the ice by then, with the crowd booing the Canadians. Sinden claims the Canadians we’re not told about the traditional salute and and apologized publicly to the Russians. “It won’t happen again,” said Sinden.

Presumably, Sinden meant the outcome of the game too.

[Now, on to Toronto].September 4

Game 2 — (filing from Toronto)

The Novosti correspondent wondered about the impact on Prime Minister Trudeau’s reelection bid next month. The president of the Toronto Maple leafs termed it “a national disaster.” The Toronto Globe and Mail columnist ate his column – lacing the newsprint with borscht.

The trauma had nothing to do with the expulsion of spies, a diplomatic snub nor even a disclosure that Canada was mixing catnip in wheat supplies shipped to the USSR. The outpouring of humility and anger represented Canada’s stunned response to the 7–3 defeat Saturday night at the hands of a hockey team from the Soviet Union. No matter what happened in three games in Canada this week, and during four matches later this month in Moscow, the Soviets have delivered a stiff body check to the Canadian national psyche. For almost 20 years Canadians have excused their losses in world hockey with the alibi that the rules barred Canada’s best players: the 300 professionals who fill national hockey league stadiums and 16 North American cities.

Canada 4-Russia 1

When Canada’s fill Esposito scored after only 30–seconds of play in game one, a national cheer rang out from St. John’s to Victoria. But it turned out to be as premature as the prediction (by the Globe columnist Dick Beddoes, and others) that Canada would win all eight games. The well-conditioned Soviets skated circles around the finest collection of hockey players ever assembled for one team. They beat the Canadians at their own game with strong individual play and goaltending, which were supposed to be Soviet weaknesses.

Humiliated by the loss, the proud NHL pros got their game together Monday night in Toronto. They forechecked the Soviets so fiercely that the vaunted Russian passing game turned into a horror show. Boston Bruin tough guy Wayne Cashman, inserted into the lineup after sitting out game one, threw elbows and shoulders around, and discouraged the fleet skated Soviets from moving with their heads down. Tony Esposito turned in some truly superior goaltending, his brother Phil scored once and set up the back breaking third goal in the 4-1 victory.

For the first 30 minutes the game was scoreless. Then just seconds before a Soviet penalty expired in the second period, New York’s Brad Park made a neat effort to keep the puck in the Russian zone. He passed it to Cashman, who entered the puck. And Esposito jammed at home from within 5 feet.

With only six seconds left in the second period, the Canadians got a big break. Defenceman Gennady Tsygankov was penalized for tripping and, when Russian scoring ace Valeri Kharlamov — the star of game one — bumped into the American referee while protesting the call, Kharlamov was sent off for 10 minutes on a misconduct penalty. With less than two minutes gone in the third period, Montreal’s speedy Yvonne Cournoyer made one of his patented breaks in on goaler Vladislav Tretiak and flicked a wrist shot into the net on a pass from New York’s Brad Park. That power play goal proved to be the winner. The Russians got their one goal five minutes later, but then the brothers Mahavolich each added a goal.

Despite the score, the Russians proved again in game two that they can be a match for the best that Canada has to offer. So exciting where the end-to-end rushes, and the saves by Esposito and Tretiak, that many NHL fans were grumbling legitimately that the Soviets were better entertainment than most expansion teams in the NHL.

Even if the Russians fail to win another game, it’s clear they have etched an impressive moral victory on the great international scoreboard. They have rejected the North American approach to hockey, with its emphasis on stars, box office and its domination by American capitalism (13 of the 16 clubs are owned in the U.S.). Instead of a system that is geared to developing a few players for the pros, the Soviets have based their success on a total concept of the athlete.

The strong Russian showing so far, in the long run, is the best thing that could happen to Canadian hockey. It may force a fundamental overhaul of the system, with the state moving more strongly into the building of rinks (as winter works projects) and the development of a solid amateur structure with top level coaching. It does not exist now.

Three Games in, some notes from the sidelines

The hockey Selects from the Soviet union skated this week in Canada on old blades, worn down almost to the tubes. When the iceman came out to make repairs on the rink during Game 3 Wednesday night, goaler Vladislav Tretiak did not head for water at the bench: he took practice shots from his mates. When the team arrived in Toronto at 2 a.m. Sunday after a gruelling game in Montreal, the comrades repaired to their dressing room in Maple Leaf Gardens to personally hang our their sweaty sweaters.

In the past such unconventional habits were greeted with chuckles of derision from the slick NHL pros – those pampered and adored stars playing for team Canada in this summit of hockey’s super powers. But not any longer. “They compare with any team in the NHL,” said Harry Sinden, shaking his head. With perspiration dripping from his brow, Sinden was trying to explain why his team had managed only a 4-4 tie in game three in Winnipeg. “We just can’t over-power this team as we all thought we could. We have a tiger by the tail.”

September 6

Game 3 — (filing from Winnipeg)

After Canada’s 7-3 humiliation at the hands of the Soviet Union Saturday, coach Harry Sinden decided to introduce some muscle into Canada’s second game line-up in Toronto Monday. Sinden turned in particular to bruising m Boston Bruin winger Wayne Cashman, who wields his “Northland” stick like a spear and his elbows like hydraulic door braces. With Soviet skaters looking for Cashman over their shoulders, Canada skated to a 4-1 win. Smiled Sinden after: “You may have noticed they didn’t have their arms around us so much this game.” Ditto game three.

Canada 4- Russia 4

Coach Bobrov made several changes of his own for Game 3 Wednesday night. Benching five regulars, Bobrov produced a “Kid Line” — all 21 — whose only previous claim to fame was leading a student team to a championship at Lake Placid last February.

The rested kids were the difference. They scored two goals — including the goal that tried the match at 4-4 — and managed to lure Cashman into a costly penalty late in the game. That happened when 21-year-old Alexander Bodunov decked “Cash” against the boards. Breathing fire, Cashman rose and slayed defenceman Yuri Shatalov on the hand with his stick in retaliation. When the referee waved Cashman to the cooler for two minutes, the winger turned his abuse on the official. The searing simply meant that Cashman was through for the night, with a 10 minute misconduct (at the time less than 10 minutes remained). With the Canadians missing an able corner man and digger, the Soviets managed to save a tie – a moral victory.

Once again it was a game of fine goaltending and superb individual play. Tony Esposito stopped 25 shots in all, including a great chest-pad save in the last 13 seconds off Alexander Maltsev. For his part, 20 year old Vladislav Tretiak committed Iceland robbery several times, stopping 38 Canadian shots. In the last period, for example, Canadian forward Paul Henderson stood all alone in front of Tretiak with the puck. As the pros are trained, Henderson gave Tretiak a ‘deke’, then lifted a point blank shot toward the net. “The man who wasn’t supposed to have a glove,” as Sinden described Tretiak, flashed out his right hand, and smothered the Henderson drive neatly.

As they did in game one, team Canada opened the scoring early Wednesday night and were leading 2-1 after the first period. They proved what their game was all about. First defensemen Gary Bergman , then Henderson, then forward Ron Ellis unleashed savage, but legal, body checks. The rattled Russians watched as New York Ranger star Jean Ratelle scored the second goal. With less than seven minutes left in the second period, Canada had a 4-2 lead on goals by Phil Esposito and Henderson. But then they felt the wrath of the Kid Line. Within four minutes, Yuri Lebedev and Bodonov had tied the game.

After the game Sinden sighed: “Aren’t we all lucky to be alive to watch a game like that. Wee. It was a 4-4 tie, that’s the way I read it.” Could the series result in a review of the way hockey is played in this country? Replied Sinden: “I think it will. I think it should. Who told us we knew all about hockey, except ourselves? They’ve got some good ideas. I haven’t seen much wrong with most things they do.”

The Soviets, who profess simply to be in Canada to learn, apparently took a slightly different angle. Coach Bobrov stressed that his Kid Line was getting its first real significant test. Naming several experienced pros who didn’t make the trip to Canada, Bobrov vowed: “The games in Moscow should be more difficult.” As for Sinden, he was thinking only of Friday night’s game in Vancouver. “Each game,” he said, “is a monumental task in itself. We are not even thinking about Moscow yet.” With that, Sinden headed for his hotel, some scotch and much contemplation.

The Cheap Seats

Three Games in, some notes from the sidelines

The hockey Selects from the Soviet union skated this week in Canada on old blades, worn down almost to the tubes. When the iceman came out to make repairs on the rink during Game 3 Wednesday night, goaler Vladislav Tretiak did not head for water at the bench: he took practice shots from his mates. When the team arrived in Toronto at 2 a.m. Sunday after a gruelling game in Montreal, the comrades repaired to their dressing room in Maple Leaf Gardens to personally hang our their sweaty sweaters.

In the past such unconventional habits were greeted with chuckles of derision from the slick NHL pros – those pampered and adored stars playing for team Canada in this summit of hockey’s super powers. But not any longer. “They compare with any team in the NHL,” said Harry Sinden, shaking his head. With perspiration dripping from his brow, Sinden was trying to explain why his team had managed only a 4-4 tie in game three in Winnipeg. “We just can’t over-power this team as we all thought we could. We have a tiger by the tail.”

Ken Dryden: A Conversation

September 6, Room 1914, Northstar Hotel, Winnipeg

Ken Dryden dropped by my hotel room today, vainly attempted to call his old Winnipeg landlady, then talked for more than an hour about what the Canada-Russia series means to hockey everywhere.

Unlike many of the NHL pros, Dryden readily admits that there are lessons to be learned from this summit of hockey super powers. “People have an absolutely newfound respect for Soviet hockey. Before the series there was a feeling, ‘we invented the game and they are interlopers.’ What has happened now is a great change that is good for hockey in general. There is a realization that they play the game differently and that they are very good. “It may lead to a realization that we should adapt our game. There just isn’t any right or wrong way. In Canada, for example, the emphasis is on individual play. Teams that don’t have great individual stars now might be advised to play a team kind of game.”Then, there’s their conditioning. They are not, after all, a big team. But in a collision on the ice it’s 50-50 as to who’s going to end up off their feet.”

Dryden makes clear that he doesn’t consider adaptation a one-way street leading into Maple Leaf Gardens. The Soviets still have weaknesses which he thinks they could correct on the basis of this series. Their goaltenders, for example, don’t roam behind the net to stop the puck for the defencemen. “This is ironic, ” adds Dryden, “because they play such a possession kind of game. But often they give up the puck when it goes behind their net.”

The former [Ralph] Nader Raider also gives the Soviets low marks on shooting. “Because they play such a team game,” he notes, “often when they are 15 -20 feet out, coming in, they’ll pass instead of shooting – and that’s such a critical area from which to shoot.”

Dryden seems almost pleased that the early predictions about an eight- game Canadian rout haven’t panned out. “That way you wouldn’t learn anything new,” he suggests. “There’s a real sort of respect now. In the past, it was always them doing it against what we regarded to be inferior competition. But now they’re doing it against us.” The Montreal Canadiens goaler believes that the Soviet team is “definitely” capable of respectable play in the National Hockey league. “They do so many things well,” says Dryden. In fact, he wonders, will the contrast between this exciting series and a regular NHL season make the fans regard even a close fight for first place as, “dull stuff?”

Dryden facing Kharlamov, Yakushev (15)

Dryden facing Kharlamov, Yakushev (15)

Dryden feels that this series will produce a much more critical form of hockey fan. “A lot of it,” he notes, “is that the fan is told, and believes, that he is seeing the very best hockey players in the world, that it’s the best show available. At least now, there’s a question. Perhaps the fan is going to become more involved, rather than accept blindly what he is told. Fans have allowed their eyes to be opened, and it’s just great.”

What has the series told Canadians about their hockey system? “Up to now,” Dryden responds, “there has been really little coaching. It was kind of house-league hockey, where you played each other and did what came naturally. In contrast, he notes, Soviet and other European coaches actually publish books which are read by a wide variety of coaches and players. Another problem is the Canadian emphasis on individual players who have NHL potential. “A kid really has to show something by age 17 or 18,” says Dryden, “or he’s through. He’s got to show he’s Junior A material by that time. He’s got to be big. He’s got to have a good shot. But US college hockey has at least demonstrated that, as late as 22 or 23, players have potential. Here, if you don’t end up in Junior A by 18, you end up in a mediocre league.” Change, as always, will be difficult. “You have an existing system,” says Dryden diplomatically, “that isn’t going to quit by itself. There are people in junior hockey making money. The NHL teams for their part are happy to get a kid at 20 rather than waiting until he’s 22 or 23.'” And a willingness to change might even overturn some of the conventional assumptions about pre-pro hockey in Canada, Dryden suggests. “Maybe you don’t have to play 60 or 70 games,” he opines.” Maybe you could play 35 – and also go to school. Now there isn’t a reasonable chance to do both. Maybe there’ll be more tolerance for other ways that can be effective.”

Dryden views Canada’s training and scholarship programs as a hopeful start. “Hockey Canada is working very slowly at this on the college level,” he says. “But a lot of people can’t qualify because of academic requirements. Maybe you need to push it back to the high school level. If a kid really wants to play hockey, he’ll do it. He might just as well do it in school.”

Dryden isn’t sure how the funds for such a program should be raised. “It would seem that the federal government would be one way – hockey school certainly can be improved. A lot of them are summer camps where the level of instruction is poor. I am not saying it should be hockey, hockey, hockey; it is a vacation for kids, after all. But maybe the level of instruction could be raised where it’s needed.” Overriding everything, in Dryden’s view, is the opportunity for fresh air to flow through hockey minds throughout the world as result of this series. “It’s not simply a question of how we play, or how the Russians play, but what new ways there are to play hockey everywhere.” Dryden concedes that “it is too early to tell” whether such profound change in hockey will emerge from this series. “Maybe,” he admits, “the initial shock will wear off and people will just forget.” Of one thing Dryden is sure: “This kind of series should be the logical end of any hockey season. There’s no reason why it shouldn’t happen — and every reason why it should.”

September 8

The Russians on the Road (Filing from Vancouver)

When veteran forward Vyacheslav Starshinov packed his skates for Canada, he also included a novel item for a professional hockey player: a lengthy two-page psychological questionnaire on hockey which he hopes will help him gain a master’s in philosophy. [Indeed, Starshinov succeeded, and then some, becoming head of sport at Moscow’s National Research Institute]. Circulated to Team Eagleson players, hockey officials and universities, the “Dear Friend” form seeks to explore such questions as the degree of “your moral responsibility before society.” Mimeographed on two sides of a 12×17 sheet of paper it is, Starsh says, “how much it is true — and how great the sense of moral responsibility before society is” (sic).

The questionnaire underlines the double-barrelled approach to hockey by the Soviets. There is of course the game on ice, and related training. But there is also a deeply rooted ideological and philosophical underpinning, which involves a kind of psychological warfare. Clearly the Soviets capitalized on Canada’s inept scouting reports by conjuring up faulty images of a bunch of automated dimwits who had lost their goaltender. In fact, when Canadian scout Davidson wrote off goaler Tretiak, on the basis of a major loss during an exhibition game while the Canadians were in Moscow, Davidson neglected to note the probable reason for Tretiak’s poor showing. The goaler was getting married the next day, says Al Eagleson. “They really sandbagged us.”

As the Russian team leaves the bus outside the hotel Vancouver Thursday after flying in from Winnipeg, the Soviet players seem, to North American eyes at least, to be bringing the same studied, psychological approach to even the most trivial actions. They look so young. [Twenty-three players under age 27—Richard J. Bendell, 1972 Summit Series] They are far from home. Yet the team swaggers off the bus, some chomping wads of gum. They are confident, obviously, but then they bend down into the baggage hold, retrieve their own gear, and walk up to the registration desk to pick up their keys.

Not long after there is another contrast with the Canadian stars. These players like to eat, sometimes as often as four hearty feeds a day. They gulp down the buffet laid out in the hotel’s “Social Suite”. Then they head , belching down the corridor, for a walk outside the hotel. (Two stragglers to the table are denounced for their tardiness in a loud voice by a team official. “Twenty-five are held up for the two of you “, he bellows).

Although the players have had, in their view, too little time for sightseeing, they have been almost as industrious in the pursuit of celluloid as have Canadian hockey players. The night before each game in Canada, the players have gone to the movies: The Godfather in Montreal; The New Centurions in Toronto; appropriately, a western called The Revengers in Winnipeg. Their training schedule, often with twice-daily skates, prevented the players from a visit to Niagara Falls, something of a must for all junketing Soviets. But team officials did make it to the falls and, while the players watched Bond’s plastic ladies last night, the team brass saw the real thing at a strip joint. Although a full-scale shopping spree is lined up for the players in Montreal on Saturday — they are staying at the Queen Elizabeth — several of them already have bought Maple Leaf decals for wives and girlfriends. They, like the NHLers, have been regular tube watchers, concentrating particularly on the Olympic games from Munich.

Like teams the world over, the players have many of the traits of the professional athlete. Says Aggie Kukulowicz, an Air Canada rep who serves the team as interpreter and tour master, “these guys are like any other hockey team. They like to joke around and play cards on the plane.” (Aggie should know. He is an ex- New York Ranger who played for David Bauer’s national team in 1965). One of the favourite Soviet team pranks is to tack a player’s slippers to the floor while he is sleeping, producing a sidesplitting scene the next morning.

Just as team Canada is a bureaucracy, so the Soviet delegation often speaks with two voices: team officials and team coaches. Last night, for example, when Boris Kulagin, the heavy in the drama, suggested that Soviet fans were perhaps more sporting and would appreciate a good play by both teams, one team official hastened to set the record straight: “Just like fans all over the world.”

One difference in the Soviet team, according to Aggie, is that “they are great for philosophizing.” When scout Arkady Chernyshev was asked during the training camp how he expected his team to perform, he replied: “All things are known in comparison.” When I asked Kulagin whether he would like to see less passing by the Soviets around the Canadian goal, he stonewalled: “Those who don’t do anything don’t make mistakes.” Kulagin even introduced a touch of Marxist dialectics into his analysis of the series. “We came here to learn from the Canadians,” he said. “We are also quite sure that there is a lot of interest in Soviet hockey. We think that, as a result of these two opposite styles of ice hockey, there is the birth of something new, some new ideas.”

It is virtually impossible to get an accurate picture of Soviet hockey from their representatives here. Early in the Canadian training camp, I was trying to interview Kulagin about the Soviet development system. Suddenly he started asking me questions: “Who is Eagleson? What does he do?” Says Kukluwicz, “The personal side is one phase of their life you’ll never get to know.”

But some reports are available that suggest the Soviet hockey star is more equal than your average Russian. As army officers, about 13 members of the team hold pseudo meetings on military matters twice a week. The rest of the time is devoted to hockey. Many players tool around town in Volga cars and have shopping rights at the foreign currency stores. I noticed that several players wore Italian shoes, and the rest of their wardrobe breaks the baggy-pants stereotype.

In the USSR, Soviet assurances to the contrary, senior hockey is a pursuit for 11-months each year. In 1967, for example, Kuklawicz, then stationed in Moscow, remembers watching the opening game of the season on July 5 – and the final game May 29, 1968. External‘s second secretary in Moscow, Gary Smith, confirms that the players only take June off for rest.

The Soviet system is based mainly on a national regime of athletic clubs. The bigger ones, like Spartak and Dynamo, offer programs in all sports and at all levels. The state ‘recommends’, for example, that kids start playing hockey at least by 10. (That’s when Eugeny Zimin started; Tretiak started at 11). More than 30,000 schoolboy teams compete each year in the “Golden puck” championships — a program that moves from school-to district-to city-to region-to republic-to national playoffs. In all, the Soviet way reportedly involves some two million kids between eight and 16 and about 600,000 registered players in the senior leagues playing for clubs, housing complexes, factories and trade unions. This is the reason that Toronto Sun columnist Jim Coleman predicts: “In 10 to 15 years I have no doubt that we will be going to Russia to try and regain the Stanley Cup.”

There are nine teams in the Soviet ‘A’ league. It is this level that supplies the stars for the national team. To prepare for the Canadian series, for example, Soviet coaches invited 50 players to training camp. They made their picks on the basis of exhibition games, scrimmages and two international tournaments before the trip to Canada. Also working for the Soviets is the fact that three teams (Army, Spartak, Dynamo) supplied most of the current roster. Even the exhibition match between Spartak and Army, which Canadian scouts watched, included one complete Spartak line playing in this series and 13 players from the Army squad. So while Kulagin tells us he only gathered the team together on August 21, it is clear that the majority has played with or against each other for several seasons.

Evgeny Paladiev, is a prime example of the ambitious recruitment of top hockey players. He grew up in Ust Kamenogorsk, the administrative centre of Kazhakstan, 5,000 miles east of Moscow. At 10 years of age, he started skating for the team in his housing project. By 16 he had joined the town’s best squad, the Torpedoes. National recruiters noticed Palediev when he travelled to Moscow for a tournament. Three years later Evgeny joined Spartak.

Paladiev started at 10, recruiters spotted him at a tournament in Moscow

Paladiev started at 10, recruiters spotted him at a tournament in Moscow

He took correspondence courses for a while from a teacher’s college back home, the tuition of about 80 rubles per month being paid by the state. Bachelor Palediev also lived the good life in Moscow, with the rent free, three-bedroom flat and the status of an NHL star, right down to autograph hounds in the hotel lobby.

Not surprisingly, such an ambitious approach to hockey involves much discipline. In a practice once in Moscow for example, Alexander Maltsev missed a pass and, in punishment, was required to do ten rolls on the ice, diving onto his shoulder, then springing back onto his skates. Ex-coach Tarasov was even given to berating players who were on the ice while goals were scored in practice sessions. “Who is guilty, raise your hand?” he demanded in one typical incident. “What did you do wrong?” he asked the offending player. Cutting short a feeble explanation, Tarasov added: “No, no, your fault began at the other end of the ice. You covered the wrong man. Don’t make that mistake again.”

In Winnipeg this week, I also watched Kulagin putting one of the second string goalers through a private, post practice drill. Kulagin waved the panting player through a series of stops and starts – straight ahead from the net and then back, off to the right and then back, off to the left and then back. Explained Kukluwicz: “They figure that when a hockey player is tired, that’s the time to get him in shape.” One player confessed to a Canadian official this week that, if he had to do it all over again, he would become a doctor, not a hockey player. It’s clear that some Russians realize there is more to life than body checks and scoring goals.

Clearly Soviet hockey players are often no different than Canadians. A Canadian star stays out until 6 AM one morning this week at a wild party; so, sometimes do the Soviets: during one Izvestia tournament two players were dismissed because they turned up late after a night of carousing.

ç

Vladislav Tretiak: A Conversation

After the game tonight, I had a promised sit-down with Vladislav Tretiak, arranged with the help of Canadian diplomat Gary Smith, who is travelling with the team in Canada. I filed this report:

For many National Hockey League stars, Dad is the dominating figure in their careers. He built rinks in the backyard, drove them to early morning practises and stood in the snow banks while they bloodied their noses. For Soviet goaltender Vladislav Tretiak, the driving force behind his hockey ability was Moma.

When young Vladislav was growing up, his mother played bandy, sometimes known as “Russian hockey” because of its possible origin there. Later she pursued athletics as an instructor of physical culture and sport. One day during a visit to the central army club swimming pool in 1963 Vladislav spotted the colourful jerseys of the local hockey team. “I wanted to have a uniform like that”, the personable 20-year-old recalled during an interview with me after the 5-3 win over Canada in Vancouver Friday night. “First you must learn to skate,” Vladislav’s mother warned the young hopeful.

So it was that Tretiak tried out as a forward for Central Army’s second boys division when he was 11. The hitch, as Vladislav discovered, was that there were very few uniforms available. If he really wanted a sweater, Tretiak was told he would have to become a goaler. Tretiak jumped at the chance. He went between the pipes for this first game—and allowed seven goals in a losing debut. But Vladislav learned quickly: he was playing with boys two or three years older than he. Each year he moved up a division with the Central Army club. “Because I was so young,” he says, “everyone rooted for me.”

The record indicates that there was reason for the accolades: Tretiak is an “honoured Sport Master”, a two-time world champion, an Olympic gold medalist, and two-time winner of the nation’s best goaltender award. For Canadians, Tretiak will be remembered as the man who stoned the NHL’s best sharp-shooters for four games and sparked his team to an upset in the first round of the Canada-Russia series.

Tretiak: Super Star at 20

Tretiak: Super Star at 20

Tretiak is currently in the third of a five-year course at the Institute of Sports. He is a lieutenant in the Army and was married just before the trip to Canada to Tatania, an attractive blonde who is a fourth year student of Soviet literature. [She became a literature teacher]. He also has a 22-year-old brother, a physicist who has no hockey interests.

Vladislav clearly enjoys the life of a hockey star in Moscow. His eyes light up when he boasts: “I get many letters from girls, even now that I’m married. They send me flowers and used to call me up all the time.” The Tretiak still live in Vladislav’s old bachelor pad, a one bedroom flat near the Leningrad highway, just 15 minutes from the Central Army stadium. Until recently Tretiak owned two cars, an Italian Zaguly and a Moskvitch. He sold the Moskvitch recently, but relishes the fact that, as he puts it, “I stand out in the crowd as a hockey star.”