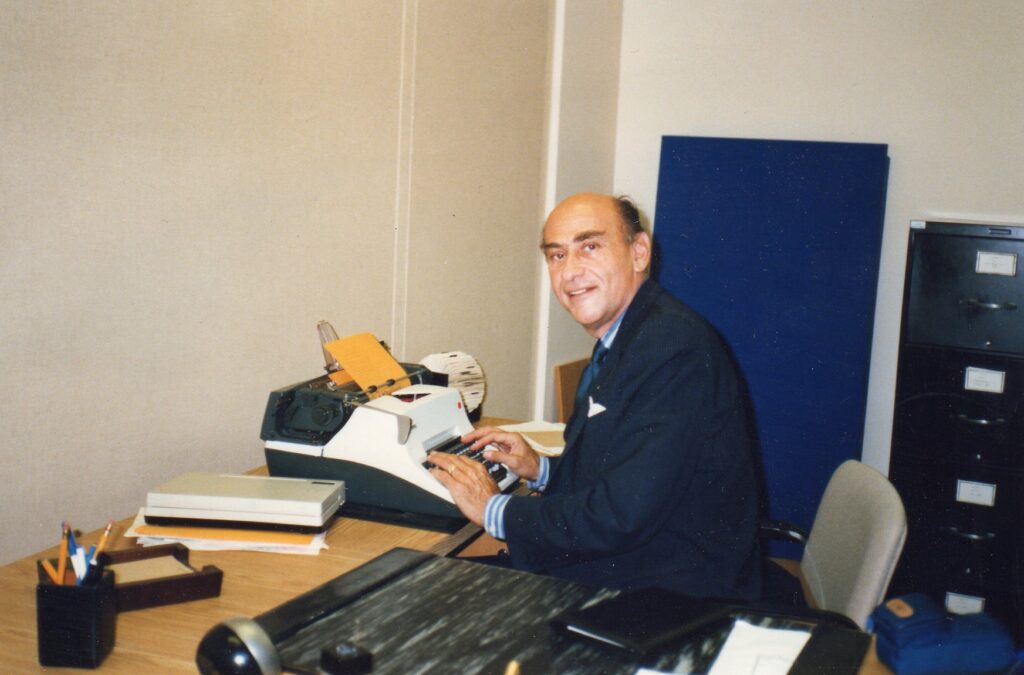

He revolutionized political reporting

In the early 1970s, Peter Newman approached me at a Time magazine party in Toronto:

“When are you going to join us at Maclean’s?”

“When you offer me a job.”

And so it was that I left the security of the most powerful magazine in North America to join a fledgling weekly magazine as Ottawa bureau chief. The operations manager confessed the company had not moved anyone, anywhere in years. But after almost a decade of toiling as an anonymous correspondent in Time‘s vineyard, the new job held out the prospect of writing my own stuff directly for publication. And Peter had rounded up a talented staff. What weighed heavily on me and colleagues Ian Urquhart and Roy MacGregor in our little bureau was that we were following in the footsteps of the man who had revolutionized political reporting in Ottawa. He was a self-described “shit disturber,” an equal opportunity assassin to all leaders. Peter died peacefully on September 8, 2023, after a long series of illnesses. In my 2018 book on the Ottawa press gallery, Power, Prime Ministers and the Press: The Battle for Truth on Parliament Hill, the chapter on Peter Newman demonstrated his impact on what was, then, a he-said-he-denied style of reportage. An excerpt:

-0-

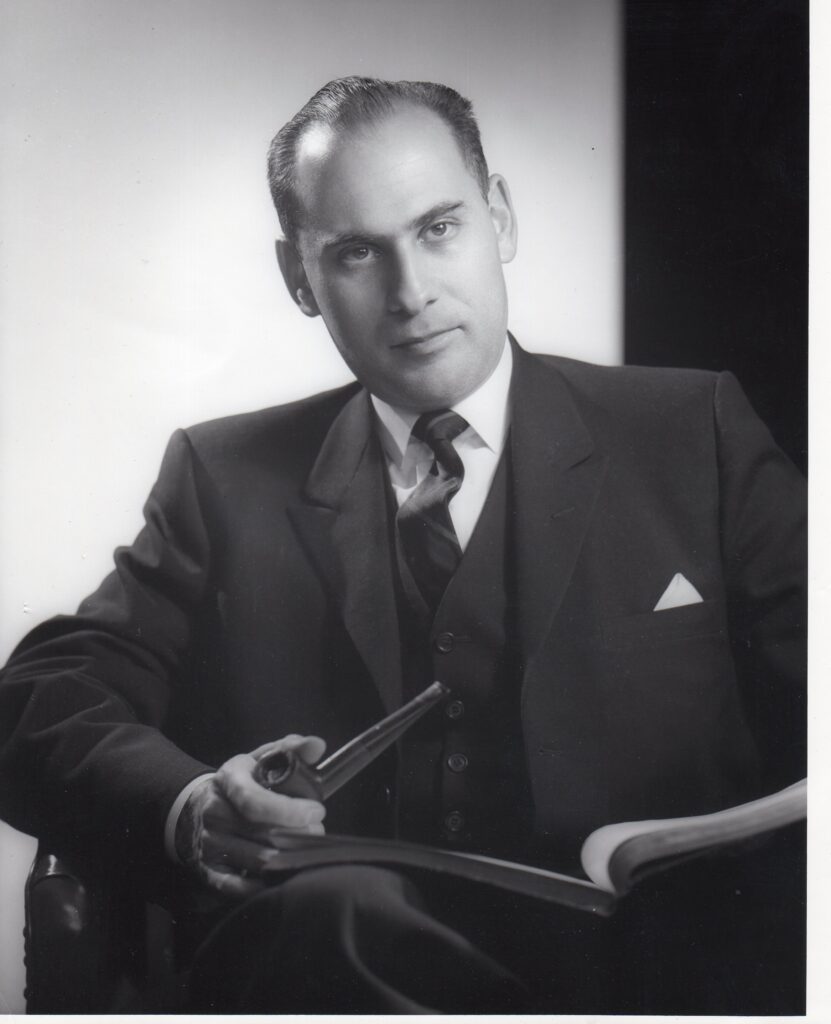

He left school in search of a paycheque after his father’s death in 1950 and his marriage to Patricia McKee the next year — he was a self-styled twenty-one-year-old virgin. He landed a lowly job at Ron McEachern’s Financial Post, summarizing corporate reports. But he had flair. In an article on a baldness treatment, he wrote, “the only thing that stops hair from falling is the floor.” His natural ability led to a posting in the Montreal bureau where his fluent French — he also spoke German and Czech — proved an asset. After a brief stint back in Toronto, Maclean’s recruited him as Ottawa columnist while incumbent Blair Fraser was on an extended European assignment.

Then John Diefenbaker entered his life — and the rest is history.

In the 1957 election campaign, when Diefenbaker toppled the St. Laurent government and ended twenty-two straight years of Liberal rule, the Tory leader managed to brand the Liberals as an arrogant party that abused the rights of Parliament. But there was more. He evoked a vision of a proud and united nation, with a northern vision for resource development, increased Canadian ownership, and reduced taxes. When new Liberal leader Lester Pearson maladroitly demanded that the Tories hand back power to the Grits in his first session, Diefenbaker seized on the debacle in the House and called a snap election for March 1958. Newman described the prime minister in full campaign mode as “a personification of the national will for whom all things were possible.” He added: “When he stood bareheaded in the rain addressing a small outdoor crowd at Penticton, B.C., I watched some of his listeners deliberately closing their umbrellas. In Fredericton, a crush of swooning women held their children up to touch him.”

Actually, Diefenbaker’s massive majority victory served only as a prelude to a decade of rancour and bitterness on the national stage, leading to new elections in 1962, 1963, 1965, and 1968. It was a period when separatism was on the rise in Quebec and other demands reverberated from the rest of the provinces. The backdrop on the global stage was the Vietnam War and women’s liberation, but Ottawa got Diefenbaker vs. Pearson. At the beginning Diefenbaker launched several positive initiatives: a nationwide highway, a new bill of rights, tax cuts, assistance to Prairie farmers, and a Commonwealth leadership role on world issues.

But even in the early months there were rumblings about dissent in Cabinet. Despite the greatest majority in Canadian history, Diefenbaker proved to be indecisive. Cabinet spent months toing and froing about the cost of building a supersonic interceptor before finally killing the CF-105, known as the Avro Arrow, along with numerous jobs and the pride of Canadian aviation. While Diefenbaker atoned for Riel and reclaimed Quebec for the Tories with fifty seats in 1958, he ignored the province by failing to appoint any francophones to senior Cabinet posts. That neglect haunted the party for a generation. He bowed to Washington and approved the installation of Bomarc missile bases for northern defence, but refused to arm them with nuclear warheads despite his NATO commitment. He picked a public fight with the Bank of Canada governor over interest rates that ended badly: James Coyne left after making his case before the Liberal-dominated Senate. Diefenbaker was unable to forge a solid relationship with U.S. president John F. Kennedy. Along the way to defeat, Diefenbaker devalued the dollar and saw seventeen of his ministers quit his Cabinet or retire. He lived for campaigning, but he failed at governing. As Newman observed: “His government never demonstrated any clear purpose except to retain power.”

Still, the gritty campaigner managed to hold the Liberals to a minority in the 1963 and 1965 elections. Then he forced his party into a messy and protracted leadership confrontation that culminated in the election of Robert Stanfield in 1967. But Diefenbaker and his rump of westerners remained in the Commons, upholding their angry vision of “One Canada.”

The gory details of Diefenbaker’s Cabinet revolt and his demise formed the heart of Newman’s 1963 book, Renegade in Power: The Diefenbaker Years. It was a sensation. Newman employed the creative devices of the novel, where the story had a beginning, a middle, and an end. There were good guys and bad girls, racy dialogue, and anecdotes from behind the curtain. And telling detail — in one illustration of the disorder that characterized the prime minister’s office, Newman wrote: “In the fall of 1957 Diefenbaker lost a personal letter from President Dwight Eisenhower, although it contained some points that required reply. After weeks of searching by his staff, Diefenbaker found the letter himself — under his bed at 24 Sussex Drive. Some eighteen months later, when Eisenhower asked Diefenbaker to Washington, his invitation went unacknowledged for three weeks.

Newman’s accounts of the Coyne crisis and the Cabinet revolt over defence policy were riveting. The detail revealed a reporter with a firm grip on the nation’s finances and public policy. At the heart of his disclosures were diaries that a dozen insiders agreed to keep, on condition that their contents would be revealed only after Diefenbaker was no longer prime minister. “Most of the book came from those notes,” Newman told me. One of the key government insiders was Roy Faibish. Officially he was executive assistant to the agricultural minister but, Newman wrote, in actual fact he was “the government’s only intellectual” — and Newman’s greatest source for the book. When I noted with surprise that Newman could get people to be so free with state secrets, he replied: “Well, so was I, frankly. It was because people who worked for Dief found him very ungrateful.”

That certainly was the word for Dief ’s reaction to Renegade. He considered suing for libel, but abandoned the idea. In a note in his own hand, preserved at the Diefenbaker Canada Centre of the University of Saskatchewan, the Chief wrote:

Then there is Newman. Here is the literary scavenger of the trash baskets on parliament hill. He is in close contact with the Liberal hierarchy and gets his briefings from them as that what [sic] he should publish…. He is an innately evil person who seems intent on tearing other people to pieces. Seems honourable people have no protection from his mind and pen. He makes his fortune in doing so. NOTE: He is an import from VIENNA!

In the beginning, Newman admired Diefenbaker. Their relations were friendly — as were the Chief ’s dealings with other key members of the press gallery. “He liked that I was from Czechoslovakia — Hitler and all that stuff — and that I survived,” Newman said. “For a while we had a really good relationship. Then I could see he was a really great orator and a great presence, but he wasn’t a great prime minister. He had never administered anything more complicated than a two-man, walk-up law office. He had a country to run, and he couldn’t.”

But the runaway success of Renegade had a profound impact on Newman as well. As Conservative political guru Dalton Camp astutely observed, “Newman’s fame soon became his notoriety: the true victim of Renegade in Power was not Diefenbaker, but Newman.” Newman admitted in his autobiography: “Truer words were never writ. The success of the book was the beginning of the end for Peter Newman and the end of the beginning for Peter C. Newman.”

Years later, after their marriage had ended, Christina wrote to Peter about the changes she saw in him after Renegade: “From that time on, the tendency already in you to make a fiction out of yourself began to distance you from reality…. The intense fame became too much for you and gradually took more and more of your real self, until you were left as nothing much but a terrified ambition.”

That strikingly brutal passage appeared in Newman’s own autobiography. When I asked him to elaborate, he was visibly uncomfortable. “All of this was mixed in with Christina and I drifting apart. That really was the end of me. It was a very happy marriage for seventeen years.” What did she mean? “Well,” he replied, “I guess what she meant was that I had illusions of grandeur. It was probably true. I don’t deny anything she wrote because I really admired her. She was incredibly intelligent.”

Bathing in his newfound celebrity after Renegade, Newman turned his sights on Lester Pearson and the Liberals after their minority government victory in 1963. And he jumped at the chance to become Ottawa columnist for the Toronto Star, following his mentor Ralph Allen who had moved from Maclean’s to be the paper’s managing editor. With that, Newman acquired a syndicated column in thirty Canadian dailies with a combined circulation of two and a half million readers, the largest of any columnist in the country. Diefenbaker and Pearson provided the grist. “During the curious decade when this odd couple ran our affairs,” Newman wrote, “the two men expected the worst of each other and were seldom disappointed.” As for his new role, “I became chief chronicler of the carnage, secure in the knowledge that the worse the government, the better the copy.”

Under Lester Pearson, things tended to go from bad to worse. His initial “sixty days of decision” featured enough indecision to give Diefenbaker, intent on toppling the minority government, one opening after another. Finance Minister Walter Gordon produced an ill-advised budget that slapped a 30 percent tax on foreign purchases of Canadian stocks and then had to admit under Commons questioning that it had been prepared with the help of three outsiders from Bay Street. Newman was getting all of the background detail down for his Star readers from the likes of Keith Davey, then national Liberal Party director, and Mike McCabe, executive assistant to Finance Minister Mitchell Sharp. He got so many scoops on Cabinet secrets that Pearson once threatened to fire any minister who leaked to Newman — a fact Newman duly reported in his column two days later.

“The sixty days of decision had unaccountably turned into ninety days of disaster and the character of the man who was to be Prime Minister of Canada for the next five years was thrown into cruel relief.” So wrote Newman in his next mega-seller, The Distemper of Our Times. Like Renegade, the book was in the style of The Making of the President, the groundbreaking1960 work by U.S. political journalist Theodore H. White. Christina was his able editor and muse. The couple became the toast of official Ottawa. They partied with Pearson and with renowned photographer Yousuf Karsh, and entertained Pierre Trudeau, the dashing minister of justice, and his date, Madeleine Gobeil, a noted journalist and professor of French literature. Newman had known Trudeau as a professor in Montreal and was among the first to promote him in print as the next Liberal leader. When Trudeau won the prize in 1968, Newman congratulated him. “Now,” he told the prime minister, “I’ll be able to obtain leaks from all the departments, not only Justice.” Trudeau retorted: “Listen, the first Cabinet leak you get, I’ll have the RCMP tap your telephone.”

Newman abandoned Ottawa in early 1969 to become the Star’s editor-in-chief. There was little love lost with his old Ottawa colleagues.

“You didn’t much like the press gallery,” I recalled. “They didn’t much like me,” Newman responded. Indeed, Newman was bitter that the gallery’s pooh-bahs denied him the traditional leave-taking gift — an engraved pewter mug. Years later he reminded me that I had arranged for his very own gallery mug. He seemed pleased.

0 Comments