Excitement mounted about the opening game in the series on September 2. My advance stories included a look at the two squads.

September 1

Rating the squads — (Filing from Montreal)

Professional hockey is machismo. The forms that scouts carry with them into the hinterlands have boxes for rating a prospect’s willingness to defend himself (sometimes called “guts”). Off the ice, players and coaches sometimes startle cabdrivers and bellboys with sharp orders that are no more aggressive than their lifestyle on the ice, but which are offensive to the untrained ear. In hockey, notice, you “get up” for the big game. Women’s role in organized hockey is virtually nil. Yet women serve as window dressing at training camps, and lobbies – and in not a few NHL hotel bedrooms.

The Canadian selects seem driven by the same macho-macho. While they pay lip service to “representing Canada” in this series, you sense that they are really here to prove themselves with the class of their profession and to preserve the honour of the National Hockey League. In perhaps a dozen casual conversations with players, rarely did they volunteer national pride as their first motivation. Says articulate Canadian goaler Ken Dryden, who will probably start the Montreal game Saturday, “we’ll have the same feelings of team and personal pride. The immediate motivation is to play well and win.”

The Russians, in contrast, say they are here primarily to learn. “What we’ve got to do is make the most of this series,” said one Soviet official on arrival in Montreal last night (August 30). As for the Canadian selects, they have to win. About 22 million Canadians, as Coach Harry Sinden notes, are “absolutely demanding it.”

While several players reckon the tension will be no greater than the final game of the NHL playoffs, Sinden and Ken Dryden disagree. “You’ll be remembered for a year for beating Russia,” says Sinden. “You’ll be remembered for the rest of your goddamn life if you lose. That’s pressure, baby.” Adds Dryden, who played against the Russians for Canada’s national team, “even if you’re not a patriot or a nationalist of any kind, the whole pageantry of the thing is such that you can’t help getting emotionally involved.”

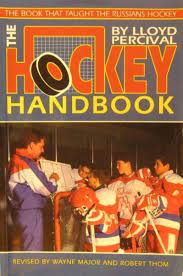

Lloyd Percival, one of Canada’s top hockey tacticians and director of Toronto’s Fitness Institute (which specializes in training programs for professional athletes) warns that the Canadian pros may not be prepared for the tension surrounding this series. “No athletes carry the emotional load that team Canada will,” Percival told us. “The reputation of the NHL is at stake. If we don’t win eight straight, it will be a moral victory for them. I’m concerned we’ll be over-emotional. We might be too tight, press too hard and start taking penalties.” In Percival’s lingo, the danger is that Canadian players could become “over–activated.”

In rating and weighing the various facets of the two teams, Percival gives Canada an overall five-point edge and predicts we’ll win the series on the basis of great individual offensive abilities and superior goaltending.

The Russians are expected to base their strategy on attack. They will start off at a fast pace and, unlike the NHL style, attempt to keep at the tempo throughout the game. Since the Russians are given the edge in conditioning, this could be important if they can keep the puck. In international play the Russians have little difficulty sustaining the brisk play: they usually have the puck 70% of the game. Against the Canadian pros, however, they may find that can’t be done. For the first time in their history, perhaps, the Russians will experience that uncomfortable sensation of defending in their own end against a sustained, two- to three-minute attack. In international play their opponents have generally managed to take only one shot, with the Russians breaking out of their end of the rink immediately.

The Russian attack will also cause the NHLers complications. The pros tend to play positional hockey on defence, with each man patrolling his “lane” of the ice to pick up his check. But the Soviets don’t skate such predictable offensive patterns. The right winger, say, might lead an attack on the left side, with the centreman trailing behind him. On defense, however, the Russians are expected to play a kind of zone. “They aren’t going to be out there playing man-for-man,” predicts Percival.

Another difference in the two styles is passing. NHL players tend to pass to an open man; the Russians will pass to get a man open. Since the Canadian selects include so many class players who tend to make the game look pretty, there may be a tendency for Canada to pass instead of shoot. This is one of the points on which Sinden has been most critical during the three week-training camp. After Saturday nights intra-squad game, for example, Sinden moaned: “Two or three times we dropped the puck when we should have shot. It was laziness. They should have headed for the goal.”

In more detail, here is a look at the two teams, their coaches, players, methods:

The Russians

A majority of the Russian selects played for the central Army team. Like most senior players in the Soviet union, the selects started training with their respective clubs in July. Several weeks before they actually take to the ice, the Russians launch a vigourous program to train the complete athlete. Under the “Tarasov plan” (named after Anatoly Tarasov), they play soccer (NHL contracts bar contact sports in the summer), lift weights to build bodies (the NHLers concentrate on drills to improve wind and legs) and work out on the trampoline.

On August 21 the Russian selects gathered as a team. They had already played in two tournaments with their own clubs. With so many players from the central Army team and another top line (Yakushev-Shadrin-Zimin) from the Spartak club, the Soviet players didn’t have to worry about adjusting to unfamiliar styles. (The Canadian team, on the other hand, claims only one complete line from one team: Hadfield-Ratelle-Gilbert.)

A tentative list of the Soviet roster provides outsiders with another revealing glimpse of the kind of confidence this team should have: many of them are veteran international champions, often with three world championships and two Olympic victories behind them. As Sinden warned his players this week: “It’s not going to be a howdy-doody time against the Russians – no way.”

Ken Dryden knows that from personal experience: after meeting the Russians in Stockholm when Canada’s National Team last appeared in the world championships, Dryden was back in the nets in Vancouver to face the returning Russians in 1969. “They completely control the puck,” he recalls. “The only times the Russians didn’t have the puck was when the referee was carrying it back to centre right after they scored.”

Dryden concedes that comparisons are difficult, since Russian and Canadian pros have yet to play common opponents, or each other. He does look for more passing from the Russians than in the NHL. “They pass more, we shoot more, and harder. You have to adjust since you don’t get as many shots.”

Another member of the Canada Selects, defenceman Brian Glennie, was in Grenoble in 1968 where he played the Soviets in the Olympics. “Many of the Russians,” he notes, “have been mates for eight to ten years. That means they function well as a unit. They are strong in the most basic skills of the game and they’ll be in good condition.”

Glennie also notes that the Russian players attempt to goad opponents. “They are very chippy with their sticks. They take cheap shots.” Says John Ferguson, the assistant coach: “They give you that little jam and run.” When a reporter told Sinden about claims that the Russians sometimes spit on opponents skating by, Sinden was horrified: “Could you just see that. Maybe we could present them with gold spittoons after it’s over.”

The real danger, of course, is that Russian goading of some kind may draw reflexive retaliation from the NHL stars — and very quick penalties. Fighting, for example, means a player is thrown out of the game. Obviously the Soviets will try to lure Canadians into stupid penalties, another reason the tension may work against Canada.

One widely held misconception is that the Russians can be intimidated by hard body checking. That is not a view shared by most of the Canadian team. “They are very strong and you can’t intimidate them,” says Glennie. Instead of intimidation tactics, Glennie advises a solid, physical approach — again, a thin line in a tension-packed series where the international officiating will favour the Soviets. The Russians, clearly, will avoid fights. “If they want to fight,” said the imperial Arkady Chernyschev, one of two Russian scouts in Canada watching the Canadian training camp, “we’ll do it later in the gym.”

Harry Sinden, who played in Oslo for the Whitby Dunlops when they won the World Championships in 1958, has some personal experience with Soviet hockey. He also faced the Russians during their first Canadian visit. “The main difference in their play,” he comments, “is the same kind of difference between their way of life and ours. They are a disciplined society and they play disciplined hockey.” When Phil Esposito was asked why NHL pros tend to sleep late, drink beer and smoke cigarettes, he quipped: “That’s their problem if they want to get up at 6 AM and run around the hotel.”

Since there are only four Canadian selects (Sinden, Dryden, Glennie and defenceman Rod Seiling of New York) with personal experience playing against the Russians, Sinden planned late this week to start going over film of Russian games with his charges. But, he notes, Canada can watch all of the films available and it still won’t be as instructive as the actual meeting of Canadian and Russian on ice. “We won’t know what we want to know about the Russians until we play them,” says Harry. “Not until we’re up close in the corners while we see their strength and attitudes.”

-0-

The scouting mission by Leaf coach John McClellan and scout Bob Davidson, in sharp contrast to the visit in Canada by the two industrious Russian ‘spies’, amounted to a little more than a goodwill tour. The Canadian ‘spies’ were only in Moscow four days and saw only two games: Spartak versus the Central Army team in Leningrad and an inter-squad game involving the Soviet selects. Spartak beat the Army team 5-2. Davidson was impressed by the way the Russians pass the puck. “They really play together as a team,” he notes. “They rarely go offside. They’re in good shape.”

Players that stood out in the brief look Davidson got were Shadrin, Yakushev and Zimin. Centreman Shadrin impressed Davidson with his forechecking; Zimin, a short, stocky right- winger, will have to be watched: he has a tendency to hang near the centre ice line, à la Yvon Cournoyer, waiting for a breakaway pass from his own end. Yakushev was outstanding in the two games. He is a good skater and puck handler. “He seemed to be dangerous whenever he had the puck,” says Davidson. Forward Maltsev with another player who impressed with his skating and puck handling.

One problem the Russians may have is in the net. They have already lost their number two goaler, Vladimir Shepevalov because of a pre-series injury. The starting goaler, Tretiak, is long and lean. Typically, for Russia, he uses his legs and is a flopper, rather than a positional player. The suspicion is that he can be beaten on blistering drives from 30–40 feet out. [That subsequently proved to be incorrect. Tretiak played all eight games and was a star of the series. It turned out that the Canadian scouts happened to see Tretiak play poorly the day after a prenuptial carousing with his mates].

Sinden ranks Valeri Kharmarlov as the team’s scoring star. He’s a good puck handler and, because of his small size, resembles Team Eagleson’s Gilbert Perreault. Veteran Anatoli Firsov, apparently, was injured recently and is not expected to play in the games in Canada.

The Canadians

Never has a finer group of hockey players been assembled anywhere in the world for one team. There are 37 in all, ranging from the obvious stars to the journeymen known mainly to insiders. Ironically the two most obvious starters – the Bobby’s Orr and Hull – won’t be in the lineups (at least Orr won’t play in Canada).

It was June 1 when Harry Sinden first started putting it all together. That was the day Al Eagleson, in his capacity as impresario of the first international Eagleson tournament, offered Harry the coaching job.

Working in Sinden’s favour is his past Olympic experience and his reputation (he coached the Bruins to the Stanley Cup in 1970) as one of the NHL’s new breed of mentors. “Sinden has a modern hockey mind,” says Lloyd Percival. “He’s not the traditionalist that so many coaches are. He’s proven he can handle stars.”

A week after his selection, Sinden turned to John Ferguson as his assistant. Fergy, along with Jean Beliveau, was a driving force behind the Montreal Canadiens in recent seasons. Like Sinden, he was not attached at the time to any NHL club. (Sinden was working with a modular housing company in Rochester, NY, which is about to go under and Fergy is prospering with a Montreal clothing manufacturer).

By July 12, Sinden had picked his last player (although five of the originals, including Hull, turned up in the rival WHA and were barred at he insistence of the NHL). “The first dozen or so players,” notes Harry, “more or less picked themselves. Any armchair hockey coach from Victoria to St. John’s could tell you who they are. The last few were the hardest, not because it’s impossible to find 35 world-class players in Canada, but because it isn’t.”

The key, once stars like Esposito, Cournoyer and Hadfield were named, was balance. Sinden chose for specific situations: for the clutch face-offs there is, for example, Stan Mikita—a late replacement for WHA-bound Derek Sanderson. For versatility there are Wayne Cashman and Jean-Paul Parisé: they can play right or left wing and, while neither is a scoring star, they are solid in the corners. There are shot-makers like Brad Park and the shot-blockers like Don Awrey. There is the finesse of Phil Esposito, Jean Ratelle, Bill Goldsworthy and Frank Mahavolich to go with the workmanship of Parisé and Ron Ellis (one of the most consistent performers in the camp so far) and Peter Mahavoilich.

In goal, what can you say about Ken Dryden, about to start his second year as Montreal’s starting netminder, Tony Esposito and Eddie Johnston? Dryden will probably start the first game, because of his previous International experience and because Montreal is home. Esposito has actually looked sharper in the training camp. Teamed with Johnston, Dryden and Esposito hold one of the keys to the expected Canadian victory. Only when the play moves to Europe, and the circular goal creases, will the Canadian goalies face a major adjustment: Esposito, particularly, likes to use the rectangular North American crease for establishing the proper defensive angles on shots.

The team arrived in camp in amazingly good condition. Most of the players were on notice about their possible selection. Because many are involved with hockey schools, and others took part in vigorous training programs (Henderson, for example, enrolled at the Percival school), there was probably less flab than at the routine NHL training camp. Because these athletes are best in the world at their trade, Sinden had little difficulty with motivation.

For just about every day now for three weeks, he has sent his men through twice-daily skating sessions, scrimmages and drills. Exercise sessions preceded each morning practice and Sinden altered the pace with three intra-squad games, a Sunday golf outing and the occasional once-a-day work out. Says Ken Dryden: “It’s the best camp I’ve ever been to. You have 35 of the best players on the same ice surface. They have pride in their ability. You’re literally forced into working hard. These people are just too good, day-to-day, to have it any other way.”

Sinden’s prime concern as the camp opened was conditioning. He worked hard on toughening up thigh and leg muscles. There were, as a result, very few of the customary early-season groin pulls. In fact, Sinden let more players off from occasional practices to return home on business then there were people missing because of serious injuries.

Says Percival of Sinden’s squad: “It’s the greatest collection of hockey players we’ve ever had in one place. Potentially it’s the greatest team ever.” The biggest question mark, as we’ve noted, Is whether they can maintain their poise and prevent the Russians from setting the game tempo throughout.

Sinden is anxiously awaiting the first game, which the experts view as the most important one. “We’ll have to see in that first game whether we are going to be able to play regular shifts. (Sinden may have to use shorter shifts to offset the Soviets conditioning advantage). If we let the pace slow down, we could be in trouble,” says Sinden.

And another question mark Involves the kind of physical game Canadian pros normally play. So far there has been very little single ‘hitting’ by the Canucks. “People who are new teammates,” explains Sinden, “don’t want flareups in the early part of the camp.” Adds Fergy: “They are just teammates right now. They are playing for Canada.” But against the Russians, the pros are expected to start throwing their weight around. “There’s no way you can play this game without hitting,” opined Fergy with a gleam in his eye. “You can’t play this game without being mad. I’m sure we’re going to be hitting the Russians.”

“I’m very concerned about the officiating,” says Sinden earnestly. “The kinds of things we do , like slamming guys into the boards, are not allowed in international play.”

0 Comments