In 1884 the twenty-five-year-old Duncan persuaded John Cameron, then editor of the Toronto Globe, to pay for articles on the World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition in New Orleans. She also sold freelance pieces on the world’s fair to the Washington Post, the London Advertiser, and the Memphis Appeal. That led to a job the next year as editorial writer for the Post in Washington and in 1886 to a breakthrough offer as a columnist at the Globe, the first woman to be hired on staff. In her first Woman’s World column on September 3 she admonished the insurance industry for denying women the same coverage as men: they could not get injury disability coverage because they tended not to have any wages, and those who worked were ruled to be frailer and more susceptible to injury than men. She wrote: “There was a time when for many reasons it was deemed inadvisable to insure women. The time has gone by, and the reasons with it. A multitude of women are now in positions of responsibility and profit…. The sooner Canadian companies understand this matter fully the better it will be for them.”

In the fashion of the day for female journalists, her Woman’s World appeared under her manly pen name, Garth Grafton, although she left no doubt about her feminist views and gender. In one early column her acerbic eye focused on newspaper advice columns for women: “Our ideal selves are constantly before us, the masculine conception, that is…. Unregenerate woman must be convinced of the evil of her ways at all costs, and if the process results in her eternal welfare, a series of well-cooked dinners may surely be his reward who brings it about.”

The ever-industrious Duncan also wrote under her real name for the literary periodicals the Week and Canada Monthly. In one critique she denounced the “vituperation” in debates about two hot topics — politics and temperance — that she felt were overshadowing scientific and literary subjects: “The Province of Ontario is one great camp of the Philistines…. We are still an eminently unliterary people.” With that, improbably, in 1887 Duncan decamped from the Globe and went to work for the Montreal Star in the Ottawa press gallery, where politics and vituperation abounded. Barred from sitting with the guys in the press gallery of the House of Commons, she sat in the Ladies’ Gallery. It was an epochal time in Canadian history: in the wake of the bitter debate about the hanging of Louis Riel, Wilfrid Laurier had become Liberal leader following Edward Blake’s second defeat at the hands of Sir John A. Macdonald.

…

After a year in the gallery, Sara Duncan also was on the move again. Itwas the era of yellow journalism, which often featured circulation-boosting, swashbuckling tales of derring-do travel by women, the riskier the more appealing. After resigning from the Star, Duncan set off on a trip around the world with fellow journalist Lily Lewis (who used the pen name Louis Lloyd). The Star published their exotic accounts: clinging to the cowcatcher of a train through the Rockies, visiting with geishas in Tokyo, riding a camel to the Great Pyramid, and taking a moonlight stroll to the Taj Mahal. The Ladies’ Pictorial in London picked up a revised version of Duncan’s pieces. That coup launched her career as a novelist.

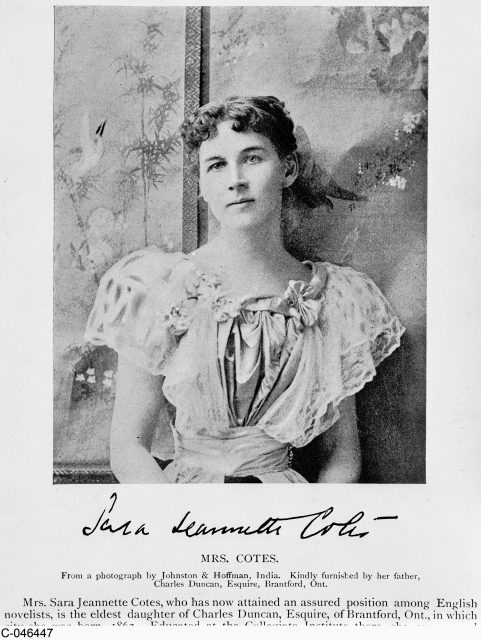

While in India, Duncan met museum official and journalist Everard Cotes and later married him after he proposed to her at the Taj Mahal. Her first book, in 1890, A Social Departure: How Orthodocia and I Went Around the World by Ourselves, was based on the world trip. Her first major work, A Daughter of Today, was the first novel published under the name she used the rest of her life, Mrs. Everard Cotes. In all, she published twenty-two books, including the autobiographical On the Other Side of the Latch, which was set in her garden in Simla, the summer seat of India’s government, where she had spent a year trying to recover from a lung infection. In 1904, critics hailed publication of The Imperialist as a departure in literary realism and celebrated the book, which sells to this day, as the best Canadian novel ever published.

She also continued to contribute articles to the India Daily News in Calcutta, where her husband was editor, and to Canadian papers such as the Winnipeg Tribune (a colour piece on the London social scene in 1912 appeared in the section called Of Interest to Women).

The couple retired to England in 1921, where Duncan, a smoker, died from a chronic lung condition at the age of sixty.

Sara Jeanette Duncan 1861-1922

0 Comments