A swagger that belies their youth

September 7

(Filing from Vancouver)

When veteran forward Vyacheslav Starshinov packed his skates for Canada, he also included a novel item for a professional hockey player: a lengthy two-page psychological questionnaire on hockey which he hopes will help him gain a master’s in philosophy. [Indeed, Starshinov succeeded, and then some, becoming head of sport at Moscow’s National Research Institute]. Circulated to Team Eagleson players, hockey officials and universities, the “Dear Friend” form seeks to explore such questions as the degree of “your moral responsibility before society.” Mimeographed on two sides of a 12×17 sheet of paper it is, Starsh says, “how much it is true — and how great the sense of moral responsibility before society is” (sic).

The questionnaire underlines the double-barrelled approach to hockey by the Soviets. There is of course the game on ice, and related training. But there is also a deeply rooted ideological and philosophical underpinning, which involves a kind of psychological warfare. Clearly the Soviets capitalized on Canada’s inept scouting reports by conjuring up faulty images of a bunch of automated dimwits who had lost their goaltender. In fact, when Canadian scout Davidson wrote off goaler Tretiak, on the basis of a major loss during an exhibition game while the Canadians were in Moscow, Davidson neglected to note the probable reason for Tretiak’s poor showing. The goaler was getting married the next day, says Al Eagleson. “They really sandbagged us.”

As the Russian team leaves the bus outside the hotel Vancouver Thursday after flying in from Winnipeg, the Soviet players seem, to North American eyes at least, to be bringing the same studied, psychological approach to even the most trivial actions. They look so young. [Twenty-three players under age 27—Richard J. Bendell, 1972 Summit Series] They are far from home. Yet the team swaggers off the bus, some chomping wads of gum. They are confident, obviously, but then they bend down into the baggage hold, retrieve their own gear, and walk up to the registration desk to pick up their keys.

Not long after there is another contrast with the Canadian stars. These players like to eat, sometimes as often as four hearty feeds a day. They gulp down the buffet laid out in the hotel’s “Social Suite”. Then they head , belching down the corridor, for a walk outside the hotel. (Two stragglers to the table are denounced for their tardiness in a loud voice by a team official. “Twenty-five are held up for the two of you “, he bellows).

Although the players have had, in their view, too little time for sightseeing, they have been almost as industrious in the pursuit of celluloid as have Canadian hockey players. The night before each game in Canada, the players have gone to the movies: The Godfather in Montreal; The New Centurions in Toronto; appropriately, a western called The Revengers in Winnipeg. Their training schedule, often with twice-daily skates, prevented the players from a visit to Niagara Falls, something of a must for all junketing Soviets. But team officials did make it to the falls and, while the players watched Bond’s plastic ladies last night, the team brass saw the real thing at a strip joint. Although a full-scale shopping spree is lined up for the players in Montreal on Saturday — they are staying at the Queen Elizabeth — several of them already have bought Maple Leaf decals for wives and girlfriends. They, like the NHLers, have been regular tube watchers, concentrating particularly on the Olympic games from Munich.

Like teams the world over, the players have many of the traits of the professional athlete. Says Aggie Kukulowicz, an Air Canada rep who serves the team as interpreter and tour master, “these guys are like any other hockey team. They like to joke around and play cards on the plane.” (Aggie should know. He is an ex- New York Ranger who played for David Bauer’s national team in 1965). One of the favourite Soviet team pranks is to tack a player’s slippers to the floor while he is sleeping, producing a sidesplitting scene the next morning.

Just as team Canada is a bureaucracy, so the Soviet delegation often speaks with two voices: team officials and team coaches. Last night, for example, when Boris Kulagin, the heavy in the drama, suggested that Soviet fans were perhaps more sporting and would appreciate a good play by both teams, one team official hastened to set the record straight: “Just like fans all over the world.”

One difference in the Soviet team, according to Aggie, is that “they are great for philosophizing.” When scout Arkady Chernyshev was asked during the training camp how he expected his team to perform, he replied: “All things are known in comparison.” When I asked Kulagin whether he would like to see less passing by the Soviets around the Canadian goal, he stonewalled: “Those who don’t do anything don’t make mistakes.” Kulagin even introduced a touch of Marxist dialectics into his analysis of the series. “We came here to learn from the Canadians,” he said. “We are also quite sure that there is a lot of interest in Soviet hockey. We think that, as a result of these two opposite styles of ice hockey, there is the birth of something new, some new ideas.”

It is virtually impossible to get an accurate picture of Soviet hockey from their representatives here. Early in the Canadian training camp, I was trying to interview Kulagin about the Soviet development system. Suddenly he started asking me questions: “Who is Eagleson? What does he do?” Says Kukluwicz, “The personal side is one phase of their life you’ll never get to know.”

But some reports are available that suggest the Soviet hockey star is more equal than your average Russian. As army officers, about 13 members of the team hold pseudo meetings on military matters twice a week. The rest of the time is devoted to hockey. Many players tool around town in Volga cars and have shopping rights at the foreign currency stores. I noticed that several players wore Italian shoes, and the rest of their wardrobe breaks the baggy-pants stereotype.

In the USSR, Soviet assurances to the contrary, senior hockey is a pursuit for 11-months each year. In 1967, for example, Kuklawicz, then stationed in Moscow, remembers watching the opening game of the season on July 5 – and the final game May 29, 1968. External‘s second secretary in Moscow, Gary Smith, confirms that the players only take June off for rest.

The Soviet system is based mainly on a national regime of athletic clubs. The bigger ones, like Spartak and Dynamo, offer programs in all sports and at all levels. The state ‘recommends’, for example, that kids start playing hockey at least by 10. (That’s when Eugeny Zimin started; Tretiak started at 11). More than 30,000 schoolboy teams compete each year in the “Golden puck” championships — a program that moves from school-to district-to city-to region-to republic-to national playoffs. In all, the Soviet way reportedly involves some two million kids between eight and 16 and about 600,000 registered players in the senior leagues playing for clubs, housing complexes, factories and trade unions. This is the reason that Toronto Sun columnist Jim Coleman predicts: “In 10 to 15 years I have no doubt that we will be going to Russia to try and regain the Stanley Cup.”

There are nine teams in the Soviet ‘A’ league. It is this level that supplies the stars for the national team. To prepare for the Canadian series, for example, Soviet coaches invited 50 players to training camp. They made their picks on the basis of exhibition games, scrimmages and two international tournaments before the trip to Canada. Also working for the Soviets is the fact that three teams (Army, Spartak, Dynamo) supplied most of the current roster. Even the exhibition match between Spartak and Army, which Canadian scouts watched, included one complete Spartak line playing in this series and 13 players from the Army squad. So while Kulagin tells us he only gathered the team together on August 21, it is clear that the majority has played with or against each other for several seasons.

Evgeny Paladiev, is a prime example of the ambitious recruitment of top hockey players. He grew up in Ust Kamenogorsk, the administrative centre of Kazhakstan, 5,000 miles east of Moscow. At 10 years of age, he started skating for the team in his housing project. By 16 he had joined the town’s best squad, the Torpedoes. National recruiters noticed Palediev when he travelled to Moscow for a tournament. Three years later Evgeny joined Spartak.

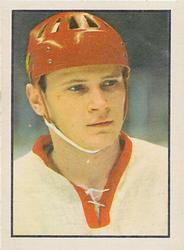

Paladiev started at 10, recruiters spotted him at a tournament in Moscow

Paladiev started at 10, recruiters spotted him at a tournament in Moscow

He took correspondence courses for a while from a teacher’s college back home, the tuition of about 80 rubles per month being paid by the state. Bachelor Palediev also lived the good life in Moscow, with the rent free, three-bedroom flat and the status of an NHL star, right down to autograph hounds in the hotel lobby.

Not surprisingly, such an ambitious approach to hockey involves much discipline. In a practice once in Moscow for example, Alexander Maltsev missed a pass and, in punishment, was required to do ten rolls on the ice, diving onto his shoulder, then springing back onto his skates. Ex-coach Tarasov was even given to berating players who were on the ice while goals were scored in practice sessions. “Who is guilty, raise your hand?” he demanded in one typical incident. “What did you do wrong?” he asked the offending player. Cutting short a feeble explanation, Tarasov added: “No, no, your fault began at the other end of the ice. You covered the wrong man. Don’t make that mistake again.”

In Winnipeg this week, I also watched Kulagin putting one of the second string goalers through a private, post practice drill. Kulagin waved the panting player through a series of stops and starts – straight ahead from the net and then back, off to the right and then back, off to the left and then back. Explained Kukluwicz: “They figure that when a hockey player is tired, that’s the time to get him in shape.” One player confessed to a Canadian official this week that, if he had to do it all over again, he would become a doctor, not a hockey player. It’s clear that some Russians realize there is more to life than body checks and scoring goals.

Clearly Soviet hockey players are often no different than Canadians. A Canadian star stays out until 6 AM one morning this week at a wild party; so, sometimes do the Soviets: during one Izvestia tournament two players were dismissed because they turned up late after a night of carousing.

0 Comments