Notes From a Soviet Practice

September 22

Central Army Club (filing from Moscow)

The sports centre of Moscow’s Central Army Club is a sprawling enclave of buildings on the western edge of downtown Moscow. Friday morning the Soviet Selects went there for a light skate to prepare for game five tonight. What went on at the rink provides an inkling of what’s behind the amazing success of the Soviet hockey program: The players rose at 8:30 AM at their special quarters outside Moscow. They did exercises, ate, then rode the bus through the gates of the central army club facilities. Apart from a theatre-like, 3000 seat ice hockey stadium, the grounds include a swimming pool, tennis courts. There are outdoor volleyball and basketball courts. Just next-door to the hockey surface, a group of six-year-olds skated fancy figures under the supervision of an instructor on a small inside rink. Back in the hockey rink, coaches Bobrov and Kulagin dismissed the starters for tonight’s game. Then they put about 15 subs through an ambitious one-hour practice. Most of the drills consisted of those patented two-on-two rushes. Holding a microphone at the side of the rink, Kulagin’s amplified instructions boomed through the empty rink. “Shto te delayesh?” (What are you doing?), Kulagin demanded of one laggard. “Bistree, bistree!” (Faster, faster), he yelled. To another player, Kulagin shouted: “You can’t do anything without skating. You’ve got to fight.” When one forward attempted some ineffective solo stickhandling, Kulagin delivered a terse lesson on teamwork: “Can’t you count to two?”

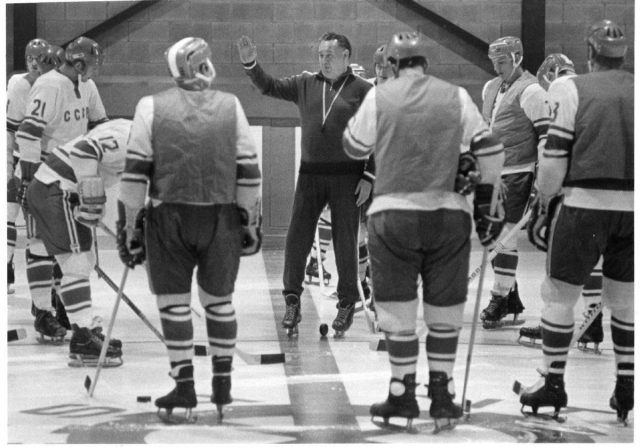

Kulagin at work:

The Soviet Union also has “rink rats.” Outside the stadium some would-be Soviet all stars were clustered trying to spot their favourite hockey players — it is not the custom here to seek autographs, apparently. One of the keenest was bright eyed Seryozha Glukhov, 13, a resident of Weston Moscow who is a defenceman on a kid’s team at the Soviet Wings sport club, an athletic centre for workers in the aircraft industry and their families. While Seryozha talked with me, he demonstrated promising form with a slap shot. He lined up a small rock, slapped it with the heel of his broken hockey stick, and sent pieces of the stone flying along the ground. He patterns his own game after Eugeny Mishakov, one of the fast skaters on the Soviet national team.

Like Seryozha, 13-year-old Igor, stood outside the Central Army Arena with a hockey stick. He says he started playing hockey at the Dynamo sport club when he was 10, the age recommended here for beginners. Since there are only three big, artificial rinks in Moscow, Igor and Seryozha will have to wait for the snowy blasts of November before getting on the ice. Once the temperature dips below freezing, however, great swatches of the city are transformed into ice sheets. In mammoth parks such as the 300-acre Lennon sports complex, they simply turn on the hoses and flood the playing fields.

Although the Soviets understandably try to cultivate the team approach in all sport — individual player profiles are not sport page features — the kids still seem to have definite views about the top players. One youngster prospecting among Canadians for bubblegum at the Lenin sports complex the other day was overheard expressing certain reservations about the personal style of Valery Kharlamov. Said little Ivan: “He is a witch.”

While Soviets sport appears to be a rather Orwellian and elitist preserve of the very talented there is no doubt about the tenacity of the elite. In a rare interview today, Boris Kulagin gave me and SI’s Mark Mulvoy a comparison of the Soviet and Canadian styles. “We think our guys worked harder,” Boris told us after the Friday morning workout. “I don’t think the Canadians had as serious an approach. The seriousness of the approach to the game is everything. The boys themselves take it seriously.”

Seemingly more affable than he was during his three-week scouting trip to Canada, Kulagin allowed as how he filled two big notebooks back to front with observations about the Canadian team. “I didn’t miss anything,” he smiled. “Everything was of interest.” Kulagin was also candid in comparing his fine young goaltender, Tretiak, to the Canadians. “The Canadians are good on the hard (slap) shots. But they are not used to stopping our style.” Harry Sinden, the embattled Canadian coach, obviously concurs.

0 Comments